-

The Lost Son of Havana (2009)

-

"**** (out of four)" - The Providence Journal

Movie review: Luis Tiant is 'The Lost Son of Havana' Friday July 10, 2009

By Michael Janusonis

Journal Arts Writer

In 2007, former Boston Red Sox pitcher Luis Tiant finally got permission to visit Cuba, his native country which he hadn't seen since he got stranded in the United States during a 1961 baseball tour and decided to stay. Cuban ruler Fidel Castro told him and other athletes who were in the United States at the time of the Bay of Pigs invasion that they could either come home and play in Cuba as amateurs or never come home again, thus turning Tiant's three-month trip into 46 years of exile.

Wishing to see his native land again before he died, however, Tiant embarked on his 2007 sentimental journey along with a film crew led by director Jonathan Hock. They recorded Tiant's emotional encounters with family members he hadn't seen in nearly half a century as well as with people he met on the street, some of whom knew of his success in the United States because Cuba is still baseball mad.

The results are the winning documentary The Lost Son of Havana, a very personal and close-up look at one of baseball's greats adrift in a place he once knew as well as the distance between the pitcher's mound and home plate at Fenway Park, but where he is now a stranger.

Hock's film, for which the Farrelly brothers served as executive producers, will largely appeal to baseball fans who remember Tiant's glory years at Fenway as well as to those who want a peek inside Cuba today. They will be rewarded with many shots of everyday street scenes with still-elegant buildings and 1950s automobiles. (The film begins a limited weeklong run Friday at a handful of theaters in the Boston orbit, including the Showcase Cinemas in Warwick.)

At the age of 67 (when Lost Son of Havana was made), Tiant has grown into a bear of a man who is affable, kindly and is sometimes bowled over by the people he meets and the sights he revisits, a Cuban Santa Claus.

On his journey, he carries along a large photograph of his father. Luis Tiant Sr., known as Lefty Tiant, was himself a star baseball player in Cuba who once dreamed of joining the major leagues in the United States where he spent 17 summers. Yet because of the times (the 1930s) and his dark skin color, Lefty never got beyond playing in America's Negro Leagues, although during an exhibition game he got to strike out Babe Ruth.

At the outset we're told by unobtrusive narrator Chris Cooper that Tiant never saw his parents in their native Cuba again, although it's only near the end of Hock's documentary when one discovers that he did see them before they died ... in the United States.

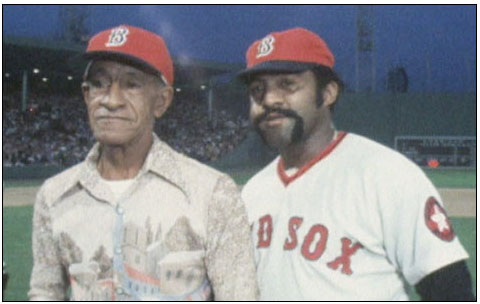

In the mid-1970s Castro himself allowed Tiant's parents to come to the U.S. to see their son play at Fenway Park and to stay as long as they wished. In one of the film's most buoyant moments we see Luis Sr. tossing out the first ball at Fenway in a game pitched by his son.

In fact, Tiant's parents stayed in the United States more than 18 months and saw him pitch in the 1975 World Series against Cincinnati. Later they both died here within days of each other, something which leads to the film's most poignant and emotional moments as Tiant recounts that dreadful time to one of his aunts in Havana while she offers him sympathy and consolation. It's actually the high point of Lost Son of Havana, which intercuts newsreel footage of Tiant's baseball career with his journey back to the place he still calls "my country," even though much of it has become alien to him.

He visits the house where he grew up in Havana and visits with relatives, sometimes dropping in unannounced. He visits the brother of former teammate Tony Oliva, who stayed in Cuba to play baseball, and to discuss the divergent ways their lives turned.

We see his several comebacks and hear testimony of Tiant's greatness from former Red Sox stars Carlton Fisk and Carl Yastrzemski. We see him sauntering over to a Havana park where the locals hang out to talk baseball and watch their reactions when one of the film crew tells them Tiant is standing behind them.

We see him at the high points of his career and the low points as Tiant tries to get back into the major leagues after being shipped to the Pittsburgh Pirates' farm team in Portland, Ore. And he made that comeback ... twice!

Hock tells us two stories with his film — Tiant's trip to the past and Tiant's own past in baseball. Fortunately, Tiant is a very engaging and colorful character who takes us along for the ride.

****The Lost Son of Havana

-

"Hock pulls off something kind of miraculous..." - Ain't It Cool News

Tribeca Film Festival '09: Mr. Beaks Journeys To Cuba With Luis Tiant, THE LOST SON OF HAVANA!

What if you reached the pinnacle of your professional career, but knew that your mother and father - the two people most responsible for helping you realize your dream - were locked away in a prison, unable to share in your success and, perhaps, unaware of your accomplishments? It'd break your heart, right?

That's essentially what Luis Tiant had to contend with throughout the bulk of his major league baseball career as a starting pitcher for the Cleveland Indians, Minnesota Twins and Boston Red Sox. While "El Tiante" was establishing himself as an unstoppable force on the mound for the Indians from 1964 to 1969 (a hapless squad that only once finished above fifth place during that period), his parents were living under the totalitarian rule of Fidel Castro in Cuba. Were they aware of his progress? Were they proud? Were they well? Save for censored correspondence, Tiant had no way of knowing how any of his loved ones were faring under Castro's dictatorship - and, save for pirate radio/TV broadcasts, they had no way of knowing whether their beloved Luis was thriving or failing in the United States.

If all you know of Tiant's career are his unique back-to-the-plate delivery* and his 1970s comeback with the Red Sox, which peaked with his heroic battle with the Big Red Machine in the 1975 World Series - or if you don't know his story at all - then you need to see Jonathan Hock's heartfelt documentary THE LOST SON OF HAVANA. Based around Tiant's 2007 return to Cuba - his first trip home in forty-six years - Hock's film works as both a Tiant family history and a humanistic, albeit deftly apolitical, examination of the poverty-stricken country during what are surely the last days of Castro's reign. Though an absolute must for baseball fans, who'll once again get caught up in the drama of that epic 1975 postseason tilt, it's also a heartbreaking account of a late-in-life family reunion, with Tiant reconnecting and, in several instances, possibly bidding farewell to the loved ones he left behind all those years ago.

The gulf between Tiant's comfortable lifestyle in the U.S., where he currently works as a pitching advisor for the Red Sox, and the squalid living conditions of his surviving aunts and uncles and cousins and nephews is, of course, stunning. It's also the basis for a good deal of dramatic tension, particularly when Tiant first begins kicking around his old neighborhood and encounters an old acquaintance. Though the man is at first pleased to see the pitching legend, he abruptly works into a rage that's fueled by resentment for Tiant leaving and the impossible conditions under which he's had to subsist for the past six decades. Though most of Tiant's relatives express no bitterness, you get the sense that there is some unspoken anger here - especially when Tiant begins handing out "extravagances" like Pepto-Bismol, chewing gum and shampoo. These gifts go over well early on, but they're mere tokens of goodwill; later on, bolder family members will hit Tiant up for cash.

But if anyone can understand this kind of practicality, it's Tiant, who affects a strictly-business swagger with his ever-present dark sunglasses and customary cigar clenched between his teeth. For much of the film, Tiant is impassive; most likely, this is byproduct of having to shut out tragic circumstances in order to excel during one of the baseball's most competitive eras. But there's a big, wounded heart beating beneath this tough exterior. And when Tiant lets his emotional guard down, it's impossible to not weep with him.

Generally, Tiant's sadness derives from the absence of family during the prime of his career. This pain is particularly acute because his father, Luis Sr., was a dominant pitcher for the Negro League's New York Cubans from 1926 to 1948. In other words, his father had already made sacrifices to help pave the way for Tiant's success in the integrated major leagues; though Luis Sr. occasionally got to show his stuff against the best in the game (there's a great story of a showdown with Babe Ruth), he was never able to do it on a consistent basis. So Tiant was living two dreams when he made it to the bigs. Sadly, most of this dream (at least until the 1970s) was little more than a rumor to the elder Luis.

What's most impressive about Hock's film is the way it refuses to use El Tiante's triumphant 1975 season as easy, unearned uplift. Yes, his domination of the Cincinnati Reds offsets a good deal of the tragedy in the pitcher's life, but it's not the end of his journey by a long shot. And while it's nice that Hock and company were crafty enough to get around the U.S.-imposed travel restrictions, Tiant's brief stay in Cuba does not wipe away forty-six years of regret - nor does it do much for the Tiants struggling to survive in the economically depressed country. And that's where Hock pulls off something kind of miraculous: rather than indulge in easy political rhetoric (or, worse, ignore the injustice altogether by closing the book on Tiant's relationship to his homeland once his visit is over), he makes this about the people. Slowly, the idea of maintaining, at the very least, the travel ban in the dying days of the Castro dictatorship becomes indefensible. At this point, it's an act of unintentional cruelty. One look at the sorry state of Cuba in Hock's film, and it's clear that the U.S. won. Want to rub this victory in Castro's face? Show his people mercy while he's still alive. Do it for the Tiants and all the other families who've spent half a century hoping to reconnect with their loved ones before it's too late.

THE LOST SON OF HAVANA premieres Thursday, April 23rd, at the Tribeca Film Festival. It will screen again on the 27th, the 30th and May 2nd.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks -

"Far more than a sports documentary" - Michael Judge/The Wall Street Journal

Stealing Home

By MICHAEL JUDGE

One of the main attractions of sports is that they're a welcome escape from the politics of the day and the things men do to one another in the name of this or that cause. Occasionally, however, the world of sports and politics collide. And when they do, it's usually without a happy outcome—think of the 1972 Munich Olympics, when 11 Israeli athletes were murdered by Palestinian terrorists; Jimmy Carter's boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics; and the subsequent Soviet boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

Pitching great Luis Tiant, the subject of ESPN's "The Lost Son of Havana."

It should come as no surprise then, that "The Lost Son of Havana," an ESPN Films documentary about Red Sox pitching great Luis Tiant's return to Cuba after 46 years of exile, is not a happy tale (Sunday, 6 p.m.-8 p.m. ET on ESPN Deportes; Monday, 10 p.m. ET on ESPN). It is, rather, the story of a refugee's rise to major-league stardom and the torment of returning home decades later to visit family on an island gulag.

"Things could have been different," says Mr. Tiant, overcome with emotion at his aunt's cramped and run-down Havana home. He is, of course, right. The wealth he accumulated in the major leagues could have helped lift his entire family out of poverty. But Castro's revolution dashed any hopes he might have had of playing professionally in his country or returning home to help support his family and the community he left behind. In 2007, he was finally allowed back into Cuba as part of a goodwill baseball game between American amateurs and retired Cuban players.

Written and directed by documentary filmmaker Jonathan Hock, "The Lost Son" begins with a shot of the 67-year-old Mr. Tiant puffing on a cigar and examining an old black-and-white photo of his father, Luis Tiant Sr., a baseball great in his own right who pitched in America's Negro League in the 1930s and '40s. Luis Sr. didn't have an overwhelming fastball but was, like his son, an absolute master of the screwball and other off-speed pitches. With his "herky-jerky" windup and off-beat delivery, he dominated the Negro League and twice defeated the Babe Ruth All-Stars in exhibition play, holding the Babe to just one single.

There's no doubt that Luis Tiant Sr. had the stuff to be a star in the majors. But by the time Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, Luis Sr.'s professional baseball career was over and he was forced to return home to Havana.

The dream of playing in the major leagues, however, lived on in his son, and in the summer of 1961 Luis Jr. left Havana for a three-month stint in the Mexican league, where he hoped to be discovered by an American scout. He quickly became a sensation and it wasn't long before the Cleveland Indians signed him to a minor-league contract.

"But that was also the summer of the invasion of the Bay of Pigs," the film's narrator, actor Chris Cooper, explains over old footage of the failed U.S. invasion. "Cuba and the United States severed relations, and Castro tightened his control over every aspect of Cuban life. Suddenly no Cuban was free to leave the island. Cubans playing baseball overseas received an ultimatum: Come home and play as amateurs in Cuba or never come home again: And so, Luis's three-month trip became 46 years of exile."

Through interviews with sportswriters, former teammates and footage from scores of games, the film documents the dramatic ups and downs of Mr. Tiant's 19-year career, including the 1970 injury (a fractured scapula) that nearly ended his playing days; his remarkable climb back to the majors (he taught himself to pitch again, it seems, by imitating his father's wild windup and off-speed pitches); and his winning starts for the Red Sox in the 1975 World Series, which Boston lost to Cincinnati 3-4.

But it is the sounds and images of his return to Cuba that are most poignant, and elevate the film to far more than a sports documentary. Antique cars and dilapidated buildings abound. Ordinary household goods are nearly impossible to come by. Like most Cubans, Mr. Tiant's aunts and cousins receive enough staple goods from the government each month to last about 15 days; they must "improvise" for the rest. Not surprisingly, the black market is thriving and U.S. dollars are the currency of choice. One relative tells Mr. Tiant, holding back tears, "We are living on cigarettes."

Knowing they're in need, Mr. Tiant brings a suitcase full of gifts and basic supplies such as clothing, toothpaste, sewing kits and medicine. And though we only see him give money to one relative, one suspects he brought a thick wad of greenbacks with him as well.

Sadly, there's an air of resentment among some. When an old neighbor says he was "forgetful" of his family, Mr. Tiant disagrees and explains that he sent gifts, money and supplies but they were always confiscated by the Cuban authorities. Still, his sense of regret at not doing enough for his family in Cuba is apparent, even though it was Luis Sr. who told him over and over again never to return, to live the life his father couldn't.

Amazingly, there's more to the story. In 1975, not long before the World Series, Castro (by all accounts a genuine baseball fan) gave Mr. Tiant's parents a special visa to travel to America. Sen. George McGovern, as he testifies in the film, hand-delivered a letter from Luis Jr. to Castro asking that he allow his parents to travel to the U.S. to see him play. For whatever reason, Castro granted his request, and Luis's parents came to America and lived with him until their all-too-early deaths the following year.

Nevertheless, a few days after his arrival in Boston, Luis Tiant Sr. was invited to throw out the ceremonial first pitch in a game against the California Angels at Fenway Park—a perfect strike. As he and his son stood together on the mound at Fenway, 30,000 adoring fans chanted "Luis! Luis! Luis!"—a glorious, and one hopes for a father and son from Havana, healing moment in baseball history.

—Mr. Judge is a freelance writer in Iowa. -

"Remarkable!" - Jeffrey Lyons/Reel Talk

HOCK HITS A HOMERUN WITH 'THE LOST SON OF HAVANA'

Posted by Jeffrey Lyons on 04/27/09

One of the 86 features screening at this year's Tribeca Film Festival is "The Lost Son of Havana," a documentary about the poignant return to Havana after 46 years by native son Luis Tiant, "El Tiante," one of the most colorful players in baseball history. He came to America just before the Bay of Pigs disaster. He went on to make the major leagues with the Cleveland Indians, pitched for the Minnesota Twins, then, from 1971 to 1978, played for the Boston Red Sox, before winding up his career with stints with the Yankees, Pirates and Angels.

The movie shows him reuniting with his surviving aunts, old Cuban teammates and friends from his neighborhood. At one point in this remarkable movie, produced by the Farrelly brothers and directed by Jonathan Hock, a group of baseball fans are arguing in a local park, trying to pick the greatest Cuban pitcher of them all. "El Duque," says one. "No, his brother Livan," says another. They name several others before one youth says, in Spanish, "What about Luis Tiant?" and Tiant is standing right behind him! It's not a staged shot, either, the director told me the other day when he and the great pitcher, #23 in your program, came in for an interview. This is a poignant movie about Tiant, his life here and in Cuba and his father, a left-handed pitcher who once faced Babe Ruth in a post season barnstorming game, and who had a distinguished career in the negro leagues. We see, in fact, the father at Fenway Park, watching his son pitch a regular season game, then in the 1975 World Series after Castro gave him and his wife permission to leave "that imprisoned isle," as JFK called Cuba. We also see memorable moments from his son's long career, a career in which he fanned more batters than hall of famers Sandy Koufax, Early Wynn, and Grover Cleveland Alexander, among others. In game five of the '75 World Series, incidentally, Tiant threw an astonishing 163 pitches, unheard of in today's game. The movie shows his modesty, his love of his adopted country but his strong feelings for his beloved birthplace and long-dormant friendships unabated by all the years. "The Lost Son of Havana" is trying to find a distributor, and here's hoping they succeed, so everyone gets to see it.

UPDATE: It's just been announced that the first Tribeca film to be sold this year is "The Lost Son of Havana." ESPN picked up broadcast rights for the documentary with plans to air it in August on ESPN and ESPN Deportes (the cable network's Spanish-language arm). -

"Quietly powerful, genuinely heartfelt..." - Steven Zeitchik/Hollywood Reporter

There's Something about Fidel: The Farrelly Bros.

Throw a Curveball

By Steven Zeitchik

Blame it on our seeing "Field of Dreams" at too impressionable an age, but baseball movies featuring fathers and sons get us every time. And so it goes with "The Lost Son of Havana," a surprisingly effective doc about the displaced Cuban pitcher Luis Tiant that premiered Thursday at Tribeca. Jonathan Hock's documentary offers a deceptively simple premise: young Cuban pitcher comes to U.S. just after Cuban revolution, enjoys fruitful Major League career but can't return home to see his family until he (and a documentary crew) finagle spots on a baseball trip back nearly fifty years later, when much of said family is gone or much older. Tiant can be a little quiet and reflective as a subject; you don't know if he's too wise or too pained by life to say much, and sometimes it seems Hock should go deeper to get at his essence. But the moments Tiant reunites with his family are quietly powerful, genuinely heartfelt stuff in which he laments with relatives time lost and lives passed by. And they're juxtaposed kind of brilliantly with dramatic on-field scenes from Tiant's comeback-filled career. (An injury robbed the reticent, roly-poly, cigar- puffing hurler of his fastball at the tender age of 29, so he developed new pitching motions that enabled him to play another decade, including three 20-win seasons and two heart-stopping World Series shutouts with the Red Sox in the 1970's). Hock captures some great slice-of-life moments in Cuba -- a park where locals gather to argue about the best Cuban baseball players of all time, for example. And the film has one of the most memorable scenes in a recent doc not named "Man on Wire" -- George McGovern, on a trip to Cuba, convinces Fidel Castro to let Tiant's father (at one time a pitcher in the Negro Leagues who had fallen on hard times back in Cuba) make the trip from Cuba to the U.S.. Tiant Sr. eventually travels to Fenway and throws out the first pitch before a game his son starts, in a moment that's right up there with Costner's "Wanna have a catch, Dad?" at end of aforementioned sentiment-filled 80's baseball pic. "Lost Son of Havana" was exec produced by the Red Sox- worshipping Peter and Bobby Farrelly, who actually ended up down in Cuba playing a game to rationalize the trip to the Cuban government. Bobby Farrelly at the Q&A (where, incidentally, Larry David wandered in, by himself, slightly foggy, it seemed, but applauding vigorously to several comments made by the Farrellys and Tiant): "You saw these guys who play against us, who cleaned our clock, and we gave them our hats and our shoes and our gloves because they didn't have anything -- our team literally walked on the bus in our underwear -- and it was the most moving thing you could imagine, because they loved this game but they didn't even have gloves or bats to play it with." There's something wistful about the film, not just the shots of 70's baseball games on long summer evenings, but the whole pace of life Hock captures down in Cuba, hardships and all. ESPN just bought the movie for a summer airing. Outside of visting the ballpark, we couldn't imagine a better way to spend a sultry August evening.

April 24, 2009 -

"Simply an astonishing and beautiful piece of storytelling..." - Tim McGonagle/NewYorkology.com

April 28, 2009

Documentaries dominate Tribeca Film Festival

The Lost Son of Havana (2009) - World Premiere

As I write for a website called NewYorkology I must reveal, in the interest of full disclosure, I'm originally from Boston and a diehard Red Sox fan. At the age of six my father took me to my first professional baseball game at Fenway Park. On the mound pitching for the Sox that day was a big man with a fierce stare and a giant bushy handlebar mustache. His windup looked exaggerated and bizarre as he released the ball from various arm slots. More importantly, the crazy junkball pitches he threw baffled hitters. The fans would chant his name "LOOOIE, LOOOIE!" as he struck out batters flailing at his pitches. He seemed bigger than life to my eyes in that summer of 1976. He wasn't just a pitcher; he was a Boston phenomenon that had people flocking to the ballpark. As baseball hall of fame writer Peter Gammons explained, "Luis Tiant was theatre unto himself."

With his thick Cuban accent, a cigar always in his mouth and a fantastic sense of humor, Tiant was an engaging character off the mound. But there was a side to him the fans never saw. Luis Tiant had not been home to his native Cuba since 1961.

The previous year he arrived in the United States as a promising young minor league prospect with the Cleveland Indians. Tiant was in the states playing in the minors when the Bay of Pigs invasion irked Castro enough to issue an ultimatum to all Cuban baseball players in the states: come home and play as amateurs, or never come home again. As their only child, his parents wanted him to pursue his dream and told him to stay in America knowing full well he may never see them again.

After a successful major league career, the 67 year-old Tiant finally gets a chance in 2007 to go home to his native Cuba from a 46 year exile. The Lost Son of Havana documents his trip back, what is left of his family and in his own words, "to see my country before I die. That's gonna complete my life." The trip back to Cuba is multi-layered with humor and heartache. His encounters with old neighbors and family are varied and fascinating. A few old friends have ambivalent feelings for Tiant. While happy for the reunions, Tiant becomes a catalyst for their anger and frustration that they couldn't leave Cuba as he did. They felt abandoned by him and the fact his letters and packages sent to them from the states were always confiscated by the Cuban government only exacerbated those feelings.

His two surviving aunts live in squalor, suffering for decades in Cuba's poverty, but are ecstatic to see him. They convey moving stories to Luis about his family during his exile, such as his mother seeing him pitch in the 1968 All-Star Game on a neighbor's TV. Watching that game or anything American was forbidden in Cuba, but the consequences of Cuban law and the weak signal didn't stop Tiant's mother. For the first time in seven years she saw her son - pitching in one of the biggest major league games of the year. His aunt told Luis his mother kept going up to the screen and touching his flickering image on the glass as tears streamed down her face. The many powerful examples of this gap between Tiant, his home and family serve only to draw the viewer into his tale.

While there are plenty of baseball stories and footage in the movie, they're relevant to the overall emotional arc and historical significance of Tiant's story. Baseball is simply the vehicle in which director Jonathan Hock captures the amazing historical depth that resonates in Tiant's life. From his father Luis "Lefty" Tiant, who was a dominating pitcher in the Negro Leagues during the 1930s and '40s to former Senator George McGovern hand delivering a letter to Fidel Castro in 1975 lobbying for Tiant's parents' release from Cuba, the Tiant saga is impressive.

Hock's documentary carefully studies Tiant's emotional conflicts of guilt and disconnect from his family and friends he left behind in impoverished Cuba. He wants to see his homeland and all its offerings, but he also deeply feels the disparity between his fortune and those he loved, left behind to suffer. Tiant tries to make sense of the complexities of his life, the hand he was dealt and the choices he made. Tiant's odyssey is long and riveting as he tries to relinquish some of the past and make peace with himself. The end result, The Lost Son of Havana, is simply an astonishing and beautiful piece of storytelling.

The story seems enormous in scope, but in fact is simply about people and the small but significant times where their lives intersect. In the beginning of the film, before his flight to Cuba, Tiant makes a stop in Miami. He pays a visit to a hilariously wise little old lady who was a close friend of his family back in Cuba years ago. They reminisce about the old times and then talk about the separation between their countries and family there — the meaning of it all. As both their eyes well with tears, the little old Cuban lady muses, "Oh my God, life is so big." As a kid (and maybe an adult too,) I always thought Luis Tiant was bigger than life. I now stand corrected. -

"Funny and Heartbreaking..." - Larry Dobrow/Maxim.com

At the Premiere: "Lost Son of Havana"

Posted Monday 04/27/2009 by Larry Dobrow

The best baseball documentaries are the ones that are sort of about baseball, but not entirely — like The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg, as much about the anti-Semitism one of the game's nascent-era sluggers had to contend with, or Baseball: A Film By Ken Burns, which shows us the lengths to which Bob Costas will go to hear himself speak. Add to that list the alternately funny and heartbreaking Lost Son of Havana, a just-debuted film that chronicles the life of should-be Hall of Fame hurler Luis Tiant.

While the flick ably encapsulates the peaks and valleys of Tiant's career — he became a multi-pitch, multi-angle machine after his fastball deserted him — what makes it sing is the tenderness with which it sketches Tiant's return to his home country of Cuba after being away for 46 years. As a young kid playing summer ball in Mexico in 1961, Tiant was given a choice: come home now or don't come at all. Following the advice of his father — a Negro League pitching legend himself — Tiant stayed in North America and eventually played in the bigs for 19 years.

Upon arriving in Cuba with camera crew in tow, Tiant is visibly affected by what he sees, especially the squalor in which his relatives have long lived. The film doesn't ever morph into a political statement, however: it focuses on family and the human connections that can't be severed by time or circumstance. When Tiant finally tears up as he prepares to return to the United States — where, especially in and around Boston, he's received as a hero — your heart breaks for the years lost. The message, conveyed without obtrusive narration or melodramatic orchestral rumbles, seems to be that you can go home again.

Meanwhile, let's give ESPN some credit here for throwing its considerable weight behind Lost Son. The network recently bought the TV rights to the documentary and plans to air it this August, following a limited release in large-city theaters.

At the Lost Son premiere during the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City last Thursday night, the vibe was more spring training than hoity-toity film festival. Answering questions alongside executive producers Peter and Bobby Farrelly (yeah, the There's Something About Mary guys) and writer/director Jon Hock, Tiant seemed almost preternaturally at ease, despite the presence of a sizable red-carpet contingent (Matt Dillon, Chris Cooper, Larry David). Stockier but with the same hall-of-fame-caliber handlebar mustache encircling his mouth, Tiant feigned a reluctance to sign autographs ("I don't like to sign paper. Paper [is what] you flush down the toilet") and, in response to a question about the modern-day pitchers who most closely resemble him, noted the similarities between himself and Pedro Martinez. "Same attitude... I look at Pedro, I look at myself."

He did, however, acknowledge one possible downside of the film's release: "Maybe because of this movie, I may not be able to go back to Cuba again." His story doesn't need yet another layer of poignancy. -

"Fascinating!" - Tom Meek/The Boston Phoenix

Review: The Lost Son of Havana

A fascinating look inside Cuba

Red Sox legend Luis Tiant left his native Cuba for pro baseball in 1961 and hadn't been back in 46 years. Then some diplomatic finagling (it's illegal for US citizens to travel to Cuba) and a loophole in the Cuban amateur-league rules (director Jonathan Hock's documentary-film crew posed as a ball team and played the Cubans) landed him on his native soil. The return is bittersweet, with recollections of his mound triumphs eclipsed by memories of his parents and a reunion with indigent surviving relatives. The look inside Cuba fascinates, as does the account of Tiant's odyssey to the majors — his father played in the Negro leagues and on one occasion whiffed the mighty Babe. -

"An experience not to be missed" - Joel Bocko/Boston Indie Movie Examiner

The Lost Son of Havana

July 13, 2009 | Boston Indie Movie Examiner | Joel Bocko

Thirty years after the chants of "Lou-eee, Lou-eee!" have faded from Fenway, six miles from the spot of a very important and long-awaited 1975 reunion, the National Amusements Showcase Cinemas in Revere screened The Lost Son of Havana in Theater 1 at 7:35 pm; one of four daily screenings for at least the remainder of the week (if it is not held over any longer). The name of the movie was left out of the "Now Playing" flyers adorning the lobby, and there weren't any placards emblazoned with large quotes from Entertainment Weekly or video installments running trailers in loops. When asked for a ticket to the film, one of the theater's employees warned, "You do know it's a documentary, right?" Apparently, this disclaimer was necessary: some customers have been complaining. No one complained on this particular night, though - the four other people in the near-empty theater seemed perfectly content with their choice of entertainment.

If you do know it's a documentary, and you don't mind, please go out and catch this moving and very enjoyable picture, which observes beloved Red Sox pitcher Luis Tiant's career, family life, and return trip to Cuba after 46 years in exile from the impoverished Communist island on which he was born and raised. Tiant's upright dignity is colored by a wry humor and pride, and also by a looming melancholy, and his charisma carries you along for the hour and forty-five minute running length. The filmmakers (director Jonathan Hock, backed by the Farrelly brothers, of all people) get out of their subject's way - the style is not flashy (though occasionally grainy film stock punctuates the video footage to represent Tiant's subjective impressions; it's a nice and subtle effect). The structure is the by now traditional call-and-response of the present (Tiant's visit to Cuba) and the past (his dogged up-and-down career in the majors); there is a narrator (the ever-dignified Chris Cooper) but he only steps in to introduce photos and footage from the 60s and 70s, tending to efface himself when the now elderly Tiant is onscreen.

Tiant is a man who has not had one athletic career, but several. First there are the years in Cuba, building up his skill, while his father - once a player in the American Negro leagues (the narration lyrically describes "seventeen summers on the backroads of America"), and a genuinely great one at that, considered by some a greater pitcher than Satchel Paige - hides in the bus roundabout across the street, watching his son play in the park despite his own disapproval of the boy's dreams. Then Tiant goes to the U.S. - and stays there when Cuba clamps down the door on ballplayers, insisting they either give up their dreams of a professional career and come home, or else abandon Cuba for a U.S. career. Tiant, with his parents' approval, chooses the latter path, and while this ensures all that is to come, to this day he seems to feel he must make excuses, and occasionally he voices mournful shame over what happened.

At any rate, success is by no means immediate. For a while he follows his father's path, playing across the Jim Crow South, and though civil rights breakthroughs were on the horizon, Tiant recalls the virulent racism of the time - another reminder that the trading-family-for-freedom narrative is not so simple as that. When he breaks in to the big leagues, he breaks in big time, pitching no-hitters, developing not one but two signature pitching styles, rising and falling between the majors and the minors, becoming a star, becoming a nobody, and becoming a star all over again...for those who are unfamiliar with the story, I will say no more, and let the movie work its magic on you. While many of Tiant's accomplishments would be at home in a feel-good sports flick, there are constant reminders that reality is messier: a powerful moment before the World Series followed by disappointment; ultimately, an inevitable fading from the scene despite comebacks; most importantly, a muted fatalism and sadness detected in Tiant's countenance.

All of this only makes the miracles that much more amazing, and the movie climaxes as Tiant's family life, the political relations of the U.S. and Cuba, and the baseball fortunes of the Red Sox converge in the autumn of '75, in a formulation that no fictional screenplay could get away with. Meanwhile, of course, the film cuts back to Tiant as a much older man, quietly surveying the baseball aficionados in Havana who, asked about the greatest Cuban exile ballplayer, come up with many other names before they remember his. His reunions and reconnections with old family and friends are emotional, but more in a quietly sad key than with a celebratory tone.

Early passages in the movie are informed by a firmly anti-Castro tone, a bit overbearing in Cooper's narration and in some of the bleak footage, but politics are neither the filmmakers' nor Tiant's concern; frustration and anger with the Castro regime's imprisonment of Cubans on their island (and in a decaying version of the past, a kind of national arrested development which foreigners seem to find romantic, but which many Cubans themselves appear frustrated by) give way to simple observation, with the emphasis on endurance and empathy, but in surprisingly uncloying ways. Repeatedly, the film eschews sentimentalism: though Tiant's family welcomes him with admiration and love, some old neighbors scold him with tears in their eyes for abandoning them - meanwhile, elderly aunts feebly remember the years lost and, in some sense, wasted, while younger cousins flat-out ask Tiant for money. Looking at their severely decayed surroundings, we do not wonder at it (and neither does he, providing the bills they require).

This is in keeping with the spirit of the man, whose determination is laced with regret, whose withheld feelings slip out from behind his reflective shades and can be glimpsed beneath his drooping gray mustache. In one scene, Tiant's narration informs us that he does not believe in an afterlife, even as the camera pans to a crucifix in his car; in this man's life, God exists to help one make it through, but there is no reward waiting on the other side. All that you have is what you make, what you've lost can never be regained, and yet one cannot linger over regrets for that very reason. That a few viewers have wandered out of the theater, apparently dismayed that they weren't seeing Transformers 2, is probably something Tiant could handle; he's been through much worse. The fact that his story is onscreen at all is triumph enough - and the experience is not to be missed. -

"Poignant, beautifully shot..."- Mike Miliard/The Boston Phoenix

Luis's Lost Years After five decades of exile, Red Sox great Luis Tiant journeys back to Cuba

By MIKE MILIARD | April 22, 2009

It had been nearly half a century since Luis Tiant stood on the Cuban soil where he was born, and where he first learned the skills that would see him become one of the greatest and most beloved pitchers in Red Sox history. But two years ago, even though he'd originally been denied a visitor's permit from both the Cuban and the US governments, he returned to the island for the first time in 46 years, as the coach of a goodwill baseball team.

There, he had joyous reunions with relatives he hadn't seen in many decades. But he also saw the rusting '56 Chevy Bel Airs and the crumbling colonial architecture. And he saw how those relatives struggle to survive on a few dollars a month.

"It was good and not good," Tiant tells the Phoenix in his thickly accented English. "You happy you come back, but you no happy with what you see. The deterioration of everything. The buildings, houses, streets. It was hard watching the way people lived. When I left, it wasn't that way. It's tough. You go down and you don't know what to do.

Cry? Or be happy because you go back to your country to see your family? It really disturb your mind."

His trip was documented by director Jonathan Hock, whose poignant, beautifully shot film The Lost Son of Havana (which was produced by the Farrelly Brothers and Kris Meyer), premieres this Saturday at the Somerville Theatre as part of Independent Film Festival Boston.

Tiant knew this would be an intensely emotional journey, and that many of the memories it dredged up would be wrenching. But he went nonetheless.

"I wanted to go and see," says the 68 year old. Otherwise, "I maybe die here before I get to go back."

Now, with Barack Obama in the White House and the headlines trumpeting a tentative thawing of US-Cuba relations — beginning with the announcement last week that the US will lift restrictions for Cuban-Americans wishing to travel and transfer money to the island — Tiant looks back on a life in which he's been exiled from his birthplace for five decades. In which he sent money home, only to have it confiscated. In which he was separated from his parents for 14 years. And he has one question: what took so long?

"I'm not a political person," says Tiant, sitting in a booth at Game On! near Fenway Park, looking sharp in a black leather jacket with a Bluetooth headset clipped to his ear and a giant 2004 World Series ring on his finger. His famous Fu Manchu is now cottony white. It's the second most expressive part of his face, after his empathic, amber-colored eyes.

Certainly, one can't picture the jovial, cigar-chomping Tiant speaking as provocatively as the Sox' Mike Lowell did back in 2006, when news reports revealed that Fidel Castro was gravely ill. "I hope he does die," said Lowell, whose parents fled the dictatorship for Puerto Rico in 1960. "Castro killed members of my family."

But if Tiant isn't especially "political," his life has been indelibly touched by politics.

By the time of the 1959 Cuban revolution, Tiant had begun to establish himself as a power-pitching phenom on the baseball-crazy island. Castro — himself a pitcher manqué— took note.

"I met him twice," says Tiant. "He used to come into the clubhouse. The last year we play in Cuba, in '61, he used to come and shake your hand."

That year, Tiant was splitting his time between playing in Cuba and the Mexican League. But in the wake of the Bay of Pigs, Castro consolidated power and locked down the island. Having abolished professional sports, he gave an ultimatum to any Cuban athlete playing abroad: return and play as an amateur or don't come home again.

And so what Tiant thought would be a three-month stint in Mexico turned into 46 years of exile. He swore he'd never go back as long as Castro was in power. But the years wore on and on. "It bother me a lot," he says. "I was the only child. My mom and dad no was young person. My father was maybe middle 50s. I thought I was never gonna see them again. It was hard, my first five years. Then, after a while, after I got my family, that made me happy in some ways: I got family to take care of now. I can't think too much or I'll go cuckoo."

Loooooeee!

The Cleveland Indians purchased Tiant's contract in 1961 for $35,000. After paying his dues in the minors, enduring segregation and racist taunts in the Jim Crow South — "they call you everything in the dictionary" — Tiant made his American professional debut in 1964.

Soon, he was dominating Major League Baseball. In 1966, he threw four straight shutouts. In 1968, he led the Majors with an obscene 1.60 ERA — the lowest in nearly 50 years — and nine shutouts. Add to that 21 wins and 264 strikeouts. Stat-wise, says famed sportswriter Peter Gammons in the film, it was "one of the five greatest seasons in the history of baseball."

But the next two seasons were marred by injuries. Cleveland gave up on him, trading Tiant to the Minnesota Twins, and soon after that he was demoted to the minors. His career looked to be all but over.

Enter the Red Sox, who took a flyer on him in 1971.

Responding to the change of scenery, Tiant completely reinvented his pitching mechanics, perfecting, in 1972, a baffling corkscrew delivery: a whirling dervish of a wind-up in which he contorted so completely that he wound up staring back at the Green Monster before uncoiling. He confounded batters with his blur of arms and legs, his three different release points, his ever-changing speeds.

It was utterly unique, and lethally effective. And it made him a folk hero, a racial unifier in busing-riven Boston. Start after start, the Fenway rafters rang out: Loooooeee!

Loooooeee!

"El Tiante," as he came to be known, posted another outstanding sub-two ERA in 1972. By 1975, when the Red Sox punched their ticket for that epochal World Series against the Big Red Machine, he flummoxed the National Leaguers with his herky-jerky motions, winning Games One and Four. In the latter, he threw an astounding 173 pitches. He struck out Babe Ruth!

Up until that time, Tiant's parents had remained sequestered in Cuba. The only glimpse they had of their son in seven years was when, in 1968, Tiant started the All-Star game and they were able to see him pitch on a fuzzy black-and-white television. "My mother bend down see my face in the TV screen," he says. "She would touch it."

But miraculously, after another seven years, when he was starting Game One of that World Series, his mother, Isabel, and his father, Luis Sr., were beaming, sitting in Fenway box seats.

Earlier that year, South Dakota senator George McGovern met with Castro in Havana. And he brought with him a letter from Massachusetts senator Edward Brooke, requesting assistance in a "matter of deep concern to myself and one of my constituents."

Tiant, Brooke wrote, was "hopeful that his parents will be able to visit . . . to see their son perform. . . . Such a reunion would be a significant indication that better understanding between our peoples is achievable."

Against all odds, Castro acceded. The Tiants could visit America. And they could stay as long as they wanted.

This was a favor no ordinary Cuban exile could have expected, of course. Not only was Castro aware of Tiant's numbers in the big leagues, he was also a fan of Tiant's father. "Lefty" Tiant, as his father was known, had played for the Negro Leagues' New York Cubans from the 1920s through the '40s. In one exhibition game, he struck out Babe Ruth. Some have opined he was a better pitcher than his son. But racism prevented him from reaching the Majors, and after his career, he returned to Cuba to work at a gas station.

Which is why it was vindication for Luis Jr. to build a dominant career in the major leagues and "do what my father never could do."

Want to tear up? Watch Tiant and his old man standing on the Fenway mound for the ceremonial first pitch, together for the first time in 14 years. Tiant holds his father's jacket, looking on proudly as the lanky septuagenarian winds up and unleashes a strike across the plate.

Having his parents finally see him pitch "made me feel good," says Tiant. "They were happy. I was proud." With them watching all through the 1976 season, he won 21 games.

But just 15 months after landing at Logan, his father died of cancer in a Boston hospital. Hours later, his wife followed him, suffering a burst aorta. A broken heart, some say.

Tiant buried both his parents on the same day.

I suffer too

"It's amazing how you got some program for 50 years, and it don't work," says Tiant of the US-Cuba policy that's remained virtually unchanged since 1961 as Castro, to the US's embarrassment, has survived.

"I don't understand that. We did it with everybody. Russia, China, all these countries around the world. Why we can't do it with Cuba? This no make sense to me. Open it for people to go down there. They can go see their family, American wanna go, they can go. Why not?"

"I understand there a lot of hard feeling," he continues. "I have hard feeling, too. I no see my father for 17 years. I suffer too. He not know my wife, or my kids, his grand kids. I got the luck, thank you God, to see them when I come here. But I lose 17 year of my family. To me, that's sad."

When Tiant did at last return to Havana, his family members reacted with mixed emotions: many were happy to at last see him, and yet unhappy that he hadn't returned sooner. "You were going to come in '91 and 2004," says one aunt in the film. Tiant's old compatriots acted much the same, achingly cognizant of their very different lots in life.

In one of the film's most powerful scenes, Tiant is approached by a former youth-league teammate. He's resentful of the career Tiant was able to make for himself: "I was mad at you. I'll tell it to you straight. Damn, Luisito, I'm pissed as hell!"

The man's neighbor gestures at his surroundings, speaking to Tiant with barely concealed pique. "Well, you see how we live here. Humbly. Struggling and working."

Tiant stands silently and listens.

"How you live with six dollars a month?", Tiant later asks me. "You gotta be kidding! But they survive. I don't know how many people can take that kind of life. But they been fighting." (It's difficult to watch his relatives' gratitude for the humble offerings he pulls from his suitcase in the film — thread, soap, toothpaste.)

Tiant knows how lucky he is to have built the life he has. He settled in the Boston area in 2001, and is now employed as an instructor for the Red Sox. A few years ago, he launched his own line of El Tiante Cigars. Occasionally, he hawks Cuban sandwiches from the El Tiante stand on Yawkey Way. Always, people stop to shake his hand. "I been happy," he says. "The best thing that happen to me is coming here."

But he still thinks often of home. And if he's heartened by these cautious recent policy changes — "at least that's a start" — he still can't shake the regret of all that lost time.

"It's sad," says Tiant. "All those years were wasted. They do what they try to do now. But why wait so long?" -

"An autumnal portrait of a hero haunted by loss and regret..." - Bill Weber/Slant Magazine

TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL: THE LOST SON OF HAVANA

By: Bill Weber | 04/26/2009

"Years is easy to say, but those are days and nights," offers an anguished Luis Tiant, famed major-league pitcher of the 1960s and '70s, returning to his boyhood streets and playing fields after a 46-year absence in The Lost Son of Havana, an autumnal portrait of a hero haunted by loss and regret. Leaving home for a three-month ball-playing stint in America at age 20 in 1961, right after the Bay of Pigs, Tiant found himself trapped by the severance of diplomatic relations, and was urged in a letter from his father—himself a former star hurler of the Cuban, Mexican, and American Negro Leagues—not to return, but to seek his professional destiny in the States. After breaking in as an All-Star flamethrower with the Cleveland Indians, Luisito came back from a freakish shoulder fracture by reinventing himself as a crafty artisan—featuring a funky windup where his head turned to centerfield, then bobbed skyward—for the Red Sox, prompting hordes of Bostonians to ritually chant his name. In a storybook climax to his family's baseball journey, Tiant's elderly parents were permitted by Castro to join their son in 1975, where they witnessed his stirring performance in the World Series.

From his sobbing embrace by elderly aunts he hadn't seen in a half-century to somber musings that "it all could have been different," El Tiante's narrative is a ready-made tearjerker, and director Jonathan Hock not only wrings them out of the poignant reunion tale, but the nearly simultaneous deaths of both of Tiant's parents the year after their unlikely furlough from Cuba ("They killed me," mourns the son). Still, the man's cigar-chomping bonhomie that so well served his mainland media profile remains magnetic, and he's authentically bemused by his "lost" status in 21st-century Havana, as when baseball aficionados in mid-debate, prompted to name the greatest native pitcher, toss out the names El Duque and Jose Contreras. As for the politics of exile, the documentary doesn't delve into ideology or advocacy beyond capturing the undertow of the poverty in his Cuban Tiant family that gnaws at their celebrated prince. "We are barely scraping by," a cousin declares frankly to Luis just before he departs the island once again, and when he peels off some U.S. bills to meet her discreet but unadorned plea, it's both the only thing he can do and, in his own mind, not nearly enough. -

"Compelling..."- Joe Bendel/The Epoch Times

Foreign Film Highlights at the Tribeca Film Festival

By Joe Bendel

Apr 23, 2009

Whether you like comedies, dramas, thrillers, or documentaries, the Tribeca Film Festival affords movie fans the unique opportunity to screen films in the company of the director and actors responsible for the work on screen.

In the spirit of the multicultural city of New York itself, this year's festival features films from 36 countries. The following are reviews of four buzz-worthy foreign films gracing the festival.

Cuban Documentary: 'The Lost Son of Havana'

The Lost Son of Havana follows retired major league baseball player Luis Tiant as he returns to Cuba for the first time in nearly 50 years.

Luis Tiant can do the impossible—he can get fans of both the New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox to agree on something. While loved and respected by Yankee fans for his two years in pinstripes, Tiant's glory years were undeniably spent pitching for the Bosox.

During his Boston stint, Tiant did everything humanly possible to end their World Series frustrations. Yet more painful for Tiant than the team's championship drought was his 46-year exile from his native Cuba. His storied career and dramatic homecoming are now documented in Jonathan Hock's The Lost Son of Havana.

Baseball is a national obsession in Cuba, and it was the Tiant family business. At one time, Luis "Lefty" Tiant Sr. had been a star pitcher for the Negro League's New York Cubans and the Cuban professional league, but his eventual obscurity left him temporarily disillusioned with the game.

Then he witnessed his son's raw talent. Unfortunately, Tiant Jr. got called to the Major Leagues just as Castro closed his iron fist around the island nation, resulting in the pitcher's long separation from friends and family.

To Hock's credit, he seems to harbor no illusions about the nature of Castro's regime. After all, he and Tiant had a difficult time getting the authorities to authorize their entry permits. They were traveling under the auspices of an American amateur baseball team playing a "goodwill" game with their Cuban counterparts.

As a condition of approval, the small crew of Lost was required to play in the match, essentially guaranteeing a lop-sided American loss, which they note, may well have been the point. Though the political situation is largely unaddressed, a corner of a Havana park dedicated to animated baseball discussions is tellingly described as the probably the only place where free speech exists in Cuba.

In between scenes of Tiant's tearful reunions with loved ones, Hock details the highlights of his eventful years in the Majors. While showing early promise, an arm injury nearly ended his career. However, the dominating fastball thrower was able to reinvent himself as a crafty pitcher, much as his father was. Time and again, Tiant was written off, but he kept clawing his way back into the league.

His is a career with many highlights, but baseball analyst Peter Gammons convincingly argues Tiant's game-four victory in the 1975 World Series was his finest moment, won on pure guts alone. To use a sports cliché (and this is certainly the time for it), as a player, Tiant had heart.

Lost is a well-crafted documentary, featuring a peppy, Cuban-inspired soundtrack by Robert Miller. The talking-head segments are a cut above average, featuring warm reminiscences by Carl Yastrzemski and Carlton Fisk that Boston fans should particularly enjoy. It also has some big names attached to it, including its producers, the Farrelly Brothers of "There's Something About Mary" fame, and narrator Chris Cooper.

Tiant is star though, and he always seems quite likable and engaging throughout the film. It is a compelling story that should have broader appeal than most sports-related documentaries. It premieres on Thursday, April 23, and screens again on April 27, April 30, and May 2. -

"LOST SON is a great movie... the Farrellys delivered the goods!" - Jerry Thornton/Barstool Sports.com

Movie Review: "Lost Son of Havana"

By Jerry Thornton | Apr 23, 2009

No list of Most Beloved Boston Athletes of All Time is worth the toner it's printed with if it doesn't include Luis Tiant in the Top 5. At his best Looie was as good as Pedro, as clutch as Schilling and Beckett and as charismatic as… well, himself. He defied comparison. No less an authority than Peter Gammons says Tiant is his favorite ballplayer, ever. And apparently he's not the only one who feels that way because in case you missed it, the Farrelly Brothers made a movie about Tiant that premiers this weekend. The movie is called "The Lost Son of Havana," it was produced by Kris Meyer who's a South Shore guy and a few weeks ago I got a private screening of it along with El Tiante himself, because working for the world's fastest growing media juggernaut is not without its privileges.

"Havana" is actually three or four different stories all rolled together into one high-quality Cuban cigar of a movie. Mainly it's about Looie's first trip back to Cuba since he defected as a 20 year old phenom in 1961. But it also tells the story of how he grew up the son of one of Cuba's national baseball heroes but had to leave his family behind for the chance to play baseball in the US. And "Lost Son" is the best account of his baseball career I've ever seen. The scenes from the mid-70s when Tiant's mom and dad got special permission to come live in Boston with their son… then watch in person while he becomes a folk hero in the ‘75 World Series… are like video pepper spray.

The Cuba scenes avoid politics, but in Cuba the politics are everywhere. Believe me nothing will make you hold on tight to your freedom faster than seeing what a country with complete government control over your life looks like. The streets of Havana are frozen in time, indistinguishable from "Godfather II." The people Tiant meet live in deprivation. One of his aunts sums it up the way only an old lady who's been through the ringer can. "Life is so big" she says. But there are funny parts throughout. Tiant meets another aunt he hasn't spoken to in 40+ years and within .5 seconds she starts kvetching about how her back is bothering her and how she hasn't been sleeping and you realize that old people squawking about their health is the universal language. Or the part when Tiant visits the park where Cuban guys stand around all day arguing baseball and it hit me that these could be my friends except they're speaking Spanish and they're not drunk.

The baseball footage is flat out incredible. Tiant starting the 1968 All Star Game when he was with Cleveland. His disasterous shoulder injury that should've ended his career until he finally re-invented himself from power pitcher to a human Swiss army knife of pitches, moves and deliveries. And the highlights of his games against the Reds, including his 170 pitch complete game epic are worth the time out of your life all by themselves. But there's a great story here as well. If you're old enough to remember El Tiante, you know what I mean. If you're not, you missed out. Either way the Farrellys delivered the goods and "Lost Son" is a great movie about a guy who's life is so big. -

"Eloquent..."- Rick Warner/Bloomberg.com

Red Sox Hero Tiant Returns to Native Cuba After 46-Year Exile Interview by Rick Warner

April 28 (Bloomberg) -- When Luis Tiant left Cuba in 1961 to play summer baseball in Mexico, he expected to be gone for three months. He didn't return for 46 years.

Tiant's long exile and emotional homecoming are the centerpiece of "The Lost Son of Havana," an eloquent documentary that's now playing at New York's Tribeca Film Festival and will air in August on ESPN. The film was produced by Bobby and Peter Farrelly, the brothers who made the comedy blockbuster "There's Something About Mary."

Nicknamed "El Tiante," the former All-Star pitcher was best known for his twisting windup, Fu Manchu mustache, stubby cigars and sterling performance for the Boston Red Sox in the 1975 World Series. Tiant won two games against the Cincinnati Reds and had a no-decision in the legendary Game 6, which Boston won in the 12th inning on Carlton Fisk's home run.

Until now, though, few people knew about his painful separation from family and friends. Barred from his native land for almost half a century because of political conflict and travel restrictions, Tiant finally was allowed to return in 2007 with an amateur baseball team.

"I wanted to go back before I die," Tiant, 68, said in a phone interview from his home near Boston. "Forty-six years is a long time to be away."

Gum, Toothpaste

Director Jonathan Hock and his small film crew followed Tiant on his weeklong trip to Cuba, where he visited two elderly aunts, old family friends and his childhood home. He was welcomed back with open arms.

"I didn't know what to expect," he said. "So many people I knew are gone now. Sometimes I want to laugh, sometimes I want to cry, sometimes I want to scream."

Tiant, whose father was a great Cuban pitcher in the U.S. Negro Leagues, was saddened by the poverty he saw in his homeland. He brought gifts of chewing gum, toothpaste, candy, lotion and clothes for his relatives, who told him of their daily struggles to survive.

"It's hard to understand the suffering, living only 90 miles from the U.S.," Tiant said. "Life is very hard there."

Old Cars

Havana today looks like it's stuck in a time warp with its 1950s vintage cars, rundown buildings and outdated TVs and radios. To accentuate that old-fashioned aura, cinematographer Alastair Christopher used an 8-millimeter camera to film scenes around the city.

"It gives you the feeling of those old home movies," Hock said at a party to celebrate the Tribeca premiere. "When you intercut that footage with the more modern-looking video, it feels like you're caught between two eras, which is what Cuba is like."

Tiant was pitching in Mexico in 1961 when the U.S. backed the failed invasion at the Bay of Pigs, leading Fidel Castro to crack down on foreign travel. If Tiant had returned to Cuba then, he knew he'd never be allowed to go to the U.S. and pitch in the major leagues. If he didn't return, he might never be allowed to come home.

Still, his parents encouraged their only child to pursue his dream.

"They knew they might never see me again, but they wanted me to take advantage of the opportunity," Tiant said.

McGovern's Help

Tiant made his major-league debut with Cleveland in 1964 and had three 20-win seasons before reaching his only World Series in 1975. Thanks to a personal request by Senator George McGovern, Castro allowed Tiant's parents to move to the U.S. and watch their son pitch in the Series.

"That was the happiest time of my life," Tiant said. "To have them here and see my success made it all worthwhile."

Tiant's reunion with his parents lasted only 15 months: His father and mother died on consecutive days in 1976. Tiant continued to pitch in the majors until 1982 and remains involved in baseball as a spring-training instructor for the Red Sox. He also has his own line of handmade "El Tiante" cigars, made by a Massachusetts-based company run by his son Danny.

As for Cuba, Tiant supports President Barack Obama's easing of travel restrictions. He would also like the president to lift the U.S. trade embargo with Cuba, which has been in effect since 1962.

"I don't care about politics, but when you do something for 50 years and it doesn't work, you should try something else," Tiant said.

-

Director Jonathan Hock on NPR's All Things Considered

The Long Road Home For A Cuban Baseball Legend

Listen to the Story

April 22, 2009

The new documentary The Lost Son of Havana tells the story of baseball legend Luis Tiant and his return to Cuba after 46 years.

Tiant was an old man, long retired from baseball, when he finally returned to his native country. Filmmaker Jonathan Hock came with him on the trip.

"He had an extraordinary need to see his family and find out if it was OK with them that he'd never come home, knowing how much they had suffered in the 46 years that he had been gone," Hock tells NPR's Robert Siegel.

A Self-Imposed Exile

Tiant had been pitching for the Mexican baseball league during the Bay of Pigs invasion. He had recently married and was planning to go back to Cuba for his honeymoon.

But his father sent him a letter saying "don't come home," explaining that there was no longer professional baseball in Cuba and that the new communist government under Fidel Castro wasn't letting anyone leave the island, Hock says.

Tiant's father told him to "give it a little time, it'll blow over and come home for your honeymoon then," Hock says.

Tiant stayed in Mexico and then went on to huge success in Major League Baseball in the United States. He pitched for several teams in his 18-year career, most notably the Boston Red Sox.

"None of them expected that it would be 46 years before Luis went home," Hock says. Tiant and his parents were reunited in the United States, but the rest of his family stayed in Cuba.

Hock says it would have been easy for Tiant to settle into life as a retired New England baseball legend, going to Fenway Park every once in a while. But Cuba pulled at him, especially the family members he had left behind.

"He needed to settle his score back home before he checked out," Hock says.

A Favorite Son Returns

The first person Tiant met in Cuba was Juan Carlos Oliva, the brother of Tony Oliva, another baseball player who had left Cuba for fame and fortune in the United States. Juan Carlos Oliva broke down in tears when talking about his brother leaving the family.

"It had broken the family's heart," Hock says.

But Oliva's family also rejoiced at Tony's success. Hock says meeting Oliva's brother and seeing his family's pain and joy prepared Tiant to meet his own family.

The film includes a touching but sobering scene at a party where Tiant meets some of his extended family. He is rich and they are poor. They soon ask him for help — in cash.

"This was one of the most uncomfortable scenes I've ever filmed. But you have to shut off your emotions and keep the camera rolling," Hock says. As Tiant is getting ready to go, his cousin takes him aside and explains that life isn't easy, they are living on cigarettes and they need more money than the government gives them.

Tiant reaches into his pocket and gives her all the Cuban money he has.

Some of Hock's filmmaker friends who looked at the rough cut of the film said he should take the scene out because it was difficult to watch. But Hock decided to keep it in: "This Cuban-American thing is very complicated. I don't think Luis was ashamed to do it; I don't think his cousin was ashamed to ask."

The moment illustrates the central tension of the story: by leaving Cuba and his family, Tiant found huge success. His family did not.

"He's been running from it his whole life," Hock says.

Returning to Cuba brings Tiant a measure of peace. "I feel better," he says in the film. "My heart is better; my head is better. I guess I can close my book now. If I die, I die happy." -

Interview with Jonathan Hock from USA Today

Documentary details Luis Tiant's return to Cuba

By Reid Cherner & Tom Weir

Luis Tiant lived the life you make movies about and Jonathan Hock has done just that.

A 20-year-old Tiant left Cuba on a trip scheduled to last a month. Forty-six years later he would finally make it back to the island.

In between, that almost half-century he would become a U.S. citizen, raise a family, play 19 seasons and win 229 games in the Major Leagues and see Fidel Castro make an exception to allow his parents, decades later, to join him to be reunited in the U.S. (Photo courtesy of 5-Hole Productions)

Hock, who wrote and directed The Lost Son of Havana talked to Game On! about following Tiant on his return to Cuba. The movie debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival and will be shown on ESPN in August.

Tell us about the movie.

It is a melancholy story and a story about coming to terms with 46 lost years. The more Luis succeeded in the Major Leagues the greater the sense of loss of over what he couldn't share with his family back in Cuba, with his countrymen back in Cuba. For every triumph there was sadness for him and until he made this trip that score was unsettled. He needed to settle that.

Did the movie turn out how you expected?

What we encountered in Cuba was beyond what we had expected in terms of the physical, economic and social state of the island. When you witness it with your own eyes, and hopefully the cameras captured this, and you meet the people and the state of deprivation they have been living in is really striking and upsetting when you are that close to it. On the other hand, the camaraderie and the openness and the friendliness and the positive spirit of the people, to experience that first hand, was something I was not expecting.

Not since Groucho has anyone used a cigar and a mustache to such great effect.

We loved the cigar. It is really a symbol of Luis' connection to his homeland. It is very symbolic of the island and we did accentuate that. The cigar was always there and we did try to bring your attention to it every now and then. Luis' story speaks in a large measure to the whole Cuban-American conflict and the whole Cuban personality that we experienced here in American for the past 50 years. The cigar has always been a prop that Castro has always used, I think it was great to sort of take it back from Castro and give it back to the people.

Tiant's father was one of Cuba's greatest pitchers was he not?

The emotional power, the thrall that Luis's father still has over people on the island is something was not something we expected from the history books. We had a photograph of Luis's father and every time we showed it to somebody they cried. Luis, having risen out of his shadow to even greater heights, is a really interesting phenomenon. Wanting to share his dream with his father, and not being able to for so long, and then being able to that is the core of the emotion of the story I think. The Cuban people have this gift of expression to be able to fully be present in their sadness and their joy at the same time and it makes for a very powerful scenes.

When Tiant is flying into Cuba there is no voice-over or conversation. Was that planned?

The decision made in the cutting room. When we saw that footage and saw that look in Luis's eyes, straining to get his first look at the island in 46 years. There were no words that were necessary. You are looking at a picture that expresses everything.

Would you say this is a happy or a sad movie?

It is both. Not one or the other. That is the incredible thing about the Cuban people. And that is the great lesson and the great gift that Luis's family in Havana, as poor as they are, as deprived as they are, that was the gift they gave to Luis, the understanding that life is sad. We can't deny that but we don't have to let that stop us from smiling and be glad for what we do have. Maybe the most important line that Luis speaks in the movie, as he's getting ready to leave his family he says to them "let's see if we can't help each other." What they have to give him is perspective in life. You don't have to dwell in the sadness, you can have peace with the sad parts of your life and the things that you've lost. You can't turn back the clock and get those lost years back. What he can have is the knowledge that everybody there still loves him and that from this point forward they can maintain the connection that he re-established with them and the joy in that going forward is no less for the sadness and the sadness in the past is no less for the joy going forward. You have two pockets in life, one for the joy and one for the sadness. You carry them both with dignity. That is Luis's message.

Would you describe this as a sports movie?

It is a story of human being an artist. His art happened to be pitching. And you can't avoid that, you want to showcase that but the movie is about him as a human being not him as an athlete. I try hard to focus hard on the human being as opposed to the field the human being happens to work in. This movie could have been about a painter, a chess player, a flutist. It happens to be about a baseball player. It is a political film, a family drama, a sports film, all those things rolled into one.

What does a sports fan get out of this movie?

For the sports fan like me, who grew up playing waffle ball and trying to do the Tiant windup, I hope that the film conjures up those memories and gives insight that you never would have had of why he was so extraordinary. It is nostalgic but it goes beyond that. It should elevate your appreciation of him to new heights.

And the non-sports fan?

I think as the saga of a Cuban-American family it tells such a powerful story. That is the magic that this guy has. To see him start the movie in such a state of loss over the past and so unsettled about the path his life has taken and then to watch him settle that score on the island where he was born and raised I think that really is uplifting. There is sadness and joy hand and hand but ultimately he says himself "today I am a free man" and he had never said that in the 46 years since he had left Cuba. He had to go back to Cuba to reclaim his freedom and he got it and you have to be happy for that. -

American Chronicle | the Lost Son of Havana Documentary Hits Home with Father-Son Baseball Story

-

The Lost Son of Havana - The Little Sleep's Blog

-

For Luis Tiant, home is where the hurt is - MiamiHerald

-

The Lost Son of havana - Film Review - Hip Hop Republican

-

The Lost Son of Havana Homepage Watch the Trailer Synopsis