The Cooler

by Jason Bellamy

by Jason Bellamy

In trying to recount the skill of running back Marcus Dupree, no one minces words. Continue reading

The Cooler

by Jason Bellamy

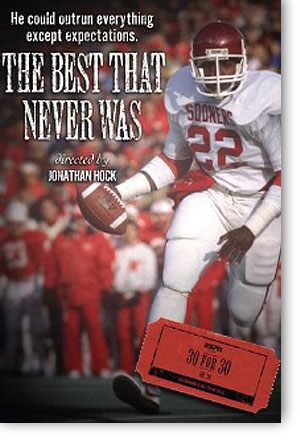

In trying to recount the skill of running back Marcus Dupree, no one minces words. One of his high school teammates says Dupree was "awesome" and could score whenever he wanted, "literally." A Mississippi newspaper reporter says that watching Dupree running through and around his prep peers was like watching NFL great Jim Brown taking on teenagers. Oklahoma University legend Barry Switzer says that Dupree was the "most gifted player" he ever coached, "bar none." And Lucious Selmon, who recruited Dupree to Oklahoma, says Dupree was the best athlete he ever saw and had the talent to be the best running back of all time. But of all the effusive assessments we encounter in Jonathan Hock's documentary The Best That Never Was, the latest edition in ESPN Films' "30 for 30" series, perhaps the most accurate one is provided by one of Dupree's childhood friends, who matter-of-factly says, "We suspected he could do anything he wanted to do." Wrapped up in that seemingly simple statement is the measure of Dupree's enormous abilities and, ironically, the making of his downfall.

Marcus Dupree's mixed blessing was that everyone who watched him play came away convinced that he was without limits. That's why Dupree had his pick of any college in the country when he graduated from his high school in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and it's also why Dupree's college football career almost immediately became defined by all he didn't do and everything he didn't have. When Dupree set a still-standing Fiesta Bowl record by rushing for 239 yards (on just 17 carries!) in Oklahoma's losing effort to Arizona State, Switzer didn't praise his freshman running back, he threw him under the bus, reasoning that if Dupree had been in better shape he could have doubled his carries and doubled his yards and, in doing so, led the Sooners to victory. Dupree had been record-setting great and somehow not great enough. Not for Switzer, anyway, who was so determined to avoid giving Dupree anything he hadn't earned that he went out of his way not to recognize the dominance that came to Depree so naturally. So it was that Dupree began wondering why the program that was so desperate to sign him in the first place withheld not just praise but also the (illegal) perks that other Sooners players were rumored to be enjoying. Influenced by family and friends who assumed that the football player who could do whatever he wanted on the field should get anything he wanted off of it, Dupree, too, started to judge his college experience according to oversized expectations. And so it came to be that instead of winning a Heisman trophy or leading Oklahoma to a national title, Dupree dropped out of Oklahoma before the end of his sophomore season. A lucrative contract with the USFL soon followed and, alas, just as quickly a devastating knee injury followed that. At the age of 20, Dupree's football career was pronounced over.

Hock revives Dupree's impressive and too brief athletic career with clarity and balance, effortlessly blending talking head interviews, archival footage and shots of Dupree revisiting his Philadelphia roots. But The Best That Never Was ranks among the upper echelon of "30 for 30" films not because it reminds us of a player that time has forgot but because it delicately demonstrates how Dupree the person was forgotten within his prime. Here's a guy who was so sought after coming out of high school that college assistants hunkered down for the long haul in Mississippi hotels while other recruiters bribed Dupree's teammates with gifts, trying to buy their influence. So intense was the contest for Dupree's services that Willie Morris wrote a book about it: The Courting of Marcus Dupree. Yet once Dupree became a Sooner, the overwhelming interest that had been paid to him as a senior was gone. No one seemed to realize how unhappy he was, and if so, no one was concerned enough to do anything about it. Dupree was a teenager being treated like a professional, not because he was that mature but because he was that skilled, as if one correlates to the other. Hock allows us to spot this failure without aggressively pointing fingers. To watch this film is to be appalled by what we take for granted: recruiters spending heaps of money in an effort to land players who come from next to nothing; players being asked to live up to their impossible reputations, or else; athletes being coerced by advisors who greedily or foolishly assume that the dominance of an athlete at 18 is a guarantee of what's to come even two years later. No wonder Dupree felt "burned out" by his sophomore year. He was being handled according to an image of his unrealized endless potential, rather than according to what he was: still just a kid.

So if I tell you that in his brief USFL career Dupree was taken advantage of by a trusted advisor who "invested" his salary in such a way that Dupree's eventual legal fees eradicated his earnings, or that after his playing days Dupree's effort to find employment required him to seek out a former Mississippi police officer who had served jail time for his role in the notorious murder of three political activists in 1964, or that now Dupree works as a truck driver, you might suspect that The Best That Never Was is a depressing film. But it isn't. Because as it turns out, the same guy who failed to achieve the long and unrivaled professional football career that everyone thought was inevitable managed to rehabilitate himself en route to a short and pedestrian professional career that, after his knee injury, even Dupree thought was impossible. All these years later, in a position that would make so many of us feel defined by missed opportunities for glory and material wealth, Dupree stands tall, proud of all that he did achieve – both in his first short career, when everything came easily, and in his even shorter comeback stint with the Los Angeles Rams when Dupree truly earned every carry and every yard through incredible effort.

Dupree's story compels because it is both unique and universal. No one followed quite the same path, yet so many athletes are stars one moment only to be forgotten the next. As Dupree looks through the dusty trophies on the mantle in his mother's home, or watches clips his high school highlights, we see not bitterness but joy – a contentment that comes from knowing that he did many things no one else ever could, even if he didn't do them for as long as people expected. Hock winds down his film with a parade of talking heads making wistful comments about all that Dupree could have been, but they reminisce without seeing all that Dupree is today. As foolish as it would be to ignore the tragedy of Dupree's football career – from his lack of a strong mentor to all that unrealized promise – it would also be a mistake overlook the beauty of Dupree's indomitable spirit almost 30 years later. When people watched Dupree play football in his prime, they saw a man who couldn't be brought down. Apparently they were right.

The Best That Never Was premieres tonight on ESPN at 8 pm ET, and will rerun frequently thereafter. The Cooler will be reviewing each film in the "30 for 30" series upon its release.

by Jason Bellamy

In trying to recount the skill of running back Marcus Dupree, no one minces words. One of his high school teammates says Dupree was "awesome" and could score whenever he wanted, "literally." A Mississippi newspaper reporter says that watching Dupree running through and around his prep peers was like watching NFL great Jim Brown taking on teenagers. Oklahoma University legend Barry Switzer says that Dupree was the "most gifted player" he ever coached, "bar none." And Lucious Selmon, who recruited Dupree to Oklahoma, says Dupree was the best athlete he ever saw and had the talent to be the best running back of all time. But of all the effusive assessments we encounter in Jonathan Hock's documentary The Best That Never Was, the latest edition in ESPN Films' "30 for 30" series, perhaps the most accurate one is provided by one of Dupree's childhood friends, who matter-of-factly says, "We suspected he could do anything he wanted to do." Wrapped up in that seemingly simple statement is the measure of Dupree's enormous abilities and, ironically, the making of his downfall.

Marcus Dupree's mixed blessing was that everyone who watched him play came away convinced that he was without limits. That's why Dupree had his pick of any college in the country when he graduated from his high school in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and it's also why Dupree's college football career almost immediately became defined by all he didn't do and everything he didn't have. When Dupree set a still-standing Fiesta Bowl record by rushing for 239 yards (on just 17 carries!) in Oklahoma's losing effort to Arizona State, Switzer didn't praise his freshman running back, he threw him under the bus, reasoning that if Dupree had been in better shape he could have doubled his carries and doubled his yards and, in doing so, led the Sooners to victory. Dupree had been record-setting great and somehow not great enough. Not for Switzer, anyway, who was so determined to avoid giving Dupree anything he hadn't earned that he went out of his way not to recognize the dominance that came to Depree so naturally. So it was that Dupree began wondering why the program that was so desperate to sign him in the first place withheld not just praise but also the (illegal) perks that other Sooners players were rumored to be enjoying. Influenced by family and friends who assumed that the football player who could do whatever he wanted on the field should get anything he wanted off of it, Dupree, too, started to judge his college experience according to oversized expectations. And so it came to be that instead of winning a Heisman trophy or leading Oklahoma to a national title, Dupree dropped out of Oklahoma before the end of his sophomore season. A lucrative contract with the USFL soon followed and, alas, just as quickly a devastating knee injury followed that. At the age of 20, Dupree's football career was pronounced over.

Hock revives Dupree's impressive and too brief athletic career with clarity and balance, effortlessly blending talking head interviews, archival footage and shots of Dupree revisiting his Philadelphia roots. But The Best That Never Was ranks among the upper echelon of "30 for 30" films not because it reminds us of a player that time has forgot but because it delicately demonstrates how Dupree the person was forgotten within his prime. Here's a guy who was so sought after coming out of high school that college assistants hunkered down for the long haul in Mississippi hotels while other recruiters bribed Dupree's teammates with gifts, trying to buy their influence. So intense was the contest for Dupree's services that Willie Morris wrote a book about it: The Courting of Marcus Dupree. Yet once Dupree became a Sooner, the overwhelming interest that had been paid to him as a senior was gone. No one seemed to realize how unhappy he was, and if so, no one was concerned enough to do anything about it. Dupree was a teenager being treated like a professional, not because he was that mature but because he was that skilled, as if one correlates to the other. Hock allows us to spot this failure without aggressively pointing fingers. To watch this film is to be appalled by what we take for granted: recruiters spending heaps of money in an effort to land players who come from next to nothing; players being asked to live up to their impossible reputations, or else; athletes being coerced by advisors who greedily or foolishly assume that the dominance of an athlete at 18 is a guarantee of what's to come even two years later. No wonder Dupree felt "burned out" by his sophomore year. He was being handled according to an image of his unrealized endless potential, rather than according to what he was: still just a kid.

So if I tell you that in his brief USFL career Dupree was taken advantage of by a trusted advisor who "invested" his salary in such a way that Dupree's eventual legal fees eradicated his earnings, or that after his playing days Dupree's effort to find employment required him to seek out a former Mississippi police officer who had served jail time for his role in the notorious murder of three political activists in 1964, or that now Dupree works as a truck driver, you might suspect that The Best That Never Was is a depressing film. But it isn't. Because as it turns out, the same guy who failed to achieve the long and unrivaled professional football career that everyone thought was inevitable managed to rehabilitate himself en route to a short and pedestrian professional career that, after his knee injury, even Dupree thought was impossible. All these years later, in a position that would make so many of us feel defined by missed opportunities for glory and material wealth, Dupree stands tall, proud of all that he did achieve – both in his first short career, when everything came easily, and in his even shorter comeback stint with the Los Angeles Rams when Dupree truly earned every carry and every yard through incredible effort.

Dupree's story compels because it is both unique and universal. No one followed quite the same path, yet so many athletes are stars one moment only to be forgotten the next. As Dupree looks through the dusty trophies on the mantle in his mother's home, or watches clips his high school highlights, we see not bitterness but joy – a contentment that comes from knowing that he did many things no one else ever could, even if he didn't do them for as long as people expected. Hock winds down his film with a parade of talking heads making wistful comments about all that Dupree could have been, but they reminisce without seeing all that Dupree is today. As foolish as it would be to ignore the tragedy of Dupree's football career – from his lack of a strong mentor to all that unrealized promise – it would also be a mistake overlook the beauty of Dupree's indomitable spirit almost 30 years later. When people watched Dupree play football in his prime, they saw a man who couldn't be brought down. Apparently they were right.

The Best That Never Was premieres tonight on ESPN at 8 pm ET, and will rerun frequently thereafter. The Cooler will be reviewing each film in the "30 for 30" series upon its release.

Pop Matters

by Cynthia Fuchs

by Cynthia Fuchs

"He didn't look like he was hustling because he was so smooth," says Leon Baxtrum. Continue reading

Pop Matters

by Cynthia Fuchs

So Much More to Play

"He didn't look like he was hustling because he was so smooth," says Leon Baxtrum. "This was a young man that was unbelievable in just about every sense of the word." The Youth League coach is remembering Marcus Dupree, whose startling speed on the football field left most everyone who saw him dumbfounded. "I just remember looking at the field and seeing 21 high school football players and Jim Brown," says Billy Watkins, a reporter for the Meridian Star. "I had never seen anybody that big running that fast. It was indescribable." Now, as he first appears in The Best That Never Was, Dupree walks. Making his way through a muddy truck-yard, he climbs into a bulldozer and sets to work.

Airing this week in ESPN's 30 for 30 series, Jonathan Hock's compelling documentary charts Dupree's trajectory from prodigiously talented high school running back to part-time truck driver. It's a story of expectation and brilliance, disappointment and misfortune. It's also a story of youthful energies misdirected and self-interested adults, of history and hope.

Dupree was born in Philadelphia, Mississippi in 1964, just three weeks before James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were murdered. For most of Marcus' life, notes the Neshoba Democrat‘s Sid Salter, "The whole county, the whole town, to a degree the whole state, bore the stain of what happened." Dupree, the film notes early on, earned the respect, and even the awe, of everyone who saw him play, including the deputy sheriff linked to the murders, Cecil Ray Price (in 1967, despite the state's best efforts not to bring charges in the case, he was convicted of violating their civil rights). "Daddy thought the world of Marcus," says Cecil Jr. Under a local newspaper headline, "Philadelphia Story: City once torn by racism unites behind black," the son recalls his own experience with his classmate, following the integration of Mississippi schools in 1970: "He would come to my house I would go to his house."

With this story and some footage of Martin Luther King Jr. (hoping that, "From the blood of those young men, our whole nation would be redeemed, that we would rise to higher heights of brotherhood and understanding"), The Best That Never Was sets a broad frame for Marcus Dupree's experience: he was never just a gifted kid. He was always carrying too many ambitions and dreams—for his family, his teammates and coaches, and a community in search of redemption.

At first, he appears so astoundingly gifted that you can see why so many people around him invested so much. Scratchy black-and-white footage of Dupree's high school games confirm what witnesses say: it does look "like everybody else was standing still and he was the only one running." His runs are so inspired and inspiring that you can see why Watkins sounds nearly rapturous: "I remember going back to the paper and thinking, ‘I have to tell them, I have to tell my readers what they have here, what they have an opportunity to see.'" Watching the film, you do feel lucky to see Dupree, and can only imagine what it must have been like to see him in person.

All that said and even if you don't know the story, the film's title indicates where Dupree is headed. Recruited by what he remembers as hundreds of colleges, he's swayed by bad advice and the sorts of "incentives" that used to be offered without much compunction. As Watkins puts it, "Players were being bought, players were being given things, it was dirty." The film includes interviews with recruiters and coaches who remember their determination to sign Dupree, how some moved to Philadelphia for months, offered cash and cars and housing for his mother Cella and younger brother Reggie (the film notes as well that Reggie suffered from cerebral palsy, which Dupree cites as a possible reason for his exceptional efforts, because "He couldn't play and run like I could run").

When, after months of back-and-forthing over where to go, he finally signs with the University of Oklahoma, Dupree is almost immediately disappointed once he arrives in Norman. Or, at least this is the story told by one of his advisors, Reverend Ken Fairley, who had been pushing him to go to the University of Southern Mississippi. While the film suggests Fairley has his own interests in Dupree's career (and indeed, he ends up with some unspecified sort of control over Dupree's money once he signs with the USFL's New Orleans Breakers in 1984), it also makes clear that none of the adults in the process was looking out for Dupree per se. He had an Uncle Curlee who pressed for one decision or another (and whom Salter describes as "shadowy"), and a coach at Oklahoma, Barry Switzer, who's introduced in his trophy room in Norman. The camera pans over prizes and awards as he notes of the team's 1985 national championship, "Marcus would have been on that team."

But he wasn't. As the film goes on to tell, Marcus was unhappy with the coaching at Oklahoma ("He wanted to move me to tight end, you know, I'm the number one running back in the country") and Switzer now says he had something like a protocol. Even though, he says, "Within the first week of practice, we know he's he best player we've got," Switzer says he decided not to use him because other players had been waiting to "get in the huddle."

This makes sense for a college team, of course, but Dupree was 19 years old, and mystified by the coaches' decisions. The documentary doesn't explain exactly how the relationships went wrong, as each interview subject has his own version of events, but the upshot is that this astonishing player was not playing, and when the team did change its offense (from a wishbone to an I formation), Dupree was again remarkable. "In every game he was busting a long run," remembers radio reporter Mick Cornett, ""A freshman putting together run after run after run. He immediately became the most popular person in Oklahoma outside of his head coach." Again, footage of Dupree—this time in color—reveals how astounding he was, and why people who saw him were so moved.

Football, as everyone knows, is a brutal game. And it is at least partly premised on luck, as this can ordain which players play, which adults counsel them, where they play and how healthy they are or stay. The Best That Never Was leaves a lot of its story off-screen, focused less on who might be responsible for what or how Marcus ended up at any particular step of his journey, than on his brilliance, however short-lived. He's injured more than once, he's confused, and he's prone to accept less than helpful recommendations. As Switzer sums up, "There was so much more to play and so much more to see we didn't get to." The question the film asks is most pertinent: who made up this "we" and where were they when Marcus Dupree needed them?

by Cynthia Fuchs

So Much More to Play

"He didn't look like he was hustling because he was so smooth," says Leon Baxtrum. "This was a young man that was unbelievable in just about every sense of the word." The Youth League coach is remembering Marcus Dupree, whose startling speed on the football field left most everyone who saw him dumbfounded. "I just remember looking at the field and seeing 21 high school football players and Jim Brown," says Billy Watkins, a reporter for the Meridian Star. "I had never seen anybody that big running that fast. It was indescribable." Now, as he first appears in The Best That Never Was, Dupree walks. Making his way through a muddy truck-yard, he climbs into a bulldozer and sets to work.

Airing this week in ESPN's 30 for 30 series, Jonathan Hock's compelling documentary charts Dupree's trajectory from prodigiously talented high school running back to part-time truck driver. It's a story of expectation and brilliance, disappointment and misfortune. It's also a story of youthful energies misdirected and self-interested adults, of history and hope.

Dupree was born in Philadelphia, Mississippi in 1964, just three weeks before James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were murdered. For most of Marcus' life, notes the Neshoba Democrat‘s Sid Salter, "The whole county, the whole town, to a degree the whole state, bore the stain of what happened." Dupree, the film notes early on, earned the respect, and even the awe, of everyone who saw him play, including the deputy sheriff linked to the murders, Cecil Ray Price (in 1967, despite the state's best efforts not to bring charges in the case, he was convicted of violating their civil rights). "Daddy thought the world of Marcus," says Cecil Jr. Under a local newspaper headline, "Philadelphia Story: City once torn by racism unites behind black," the son recalls his own experience with his classmate, following the integration of Mississippi schools in 1970: "He would come to my house I would go to his house."

With this story and some footage of Martin Luther King Jr. (hoping that, "From the blood of those young men, our whole nation would be redeemed, that we would rise to higher heights of brotherhood and understanding"), The Best That Never Was sets a broad frame for Marcus Dupree's experience: he was never just a gifted kid. He was always carrying too many ambitions and dreams—for his family, his teammates and coaches, and a community in search of redemption.

At first, he appears so astoundingly gifted that you can see why so many people around him invested so much. Scratchy black-and-white footage of Dupree's high school games confirm what witnesses say: it does look "like everybody else was standing still and he was the only one running." His runs are so inspired and inspiring that you can see why Watkins sounds nearly rapturous: "I remember going back to the paper and thinking, ‘I have to tell them, I have to tell my readers what they have here, what they have an opportunity to see.'" Watching the film, you do feel lucky to see Dupree, and can only imagine what it must have been like to see him in person.

All that said and even if you don't know the story, the film's title indicates where Dupree is headed. Recruited by what he remembers as hundreds of colleges, he's swayed by bad advice and the sorts of "incentives" that used to be offered without much compunction. As Watkins puts it, "Players were being bought, players were being given things, it was dirty." The film includes interviews with recruiters and coaches who remember their determination to sign Dupree, how some moved to Philadelphia for months, offered cash and cars and housing for his mother Cella and younger brother Reggie (the film notes as well that Reggie suffered from cerebral palsy, which Dupree cites as a possible reason for his exceptional efforts, because "He couldn't play and run like I could run").

When, after months of back-and-forthing over where to go, he finally signs with the University of Oklahoma, Dupree is almost immediately disappointed once he arrives in Norman. Or, at least this is the story told by one of his advisors, Reverend Ken Fairley, who had been pushing him to go to the University of Southern Mississippi. While the film suggests Fairley has his own interests in Dupree's career (and indeed, he ends up with some unspecified sort of control over Dupree's money once he signs with the USFL's New Orleans Breakers in 1984), it also makes clear that none of the adults in the process was looking out for Dupree per se. He had an Uncle Curlee who pressed for one decision or another (and whom Salter describes as "shadowy"), and a coach at Oklahoma, Barry Switzer, who's introduced in his trophy room in Norman. The camera pans over prizes and awards as he notes of the team's 1985 national championship, "Marcus would have been on that team."

But he wasn't. As the film goes on to tell, Marcus was unhappy with the coaching at Oklahoma ("He wanted to move me to tight end, you know, I'm the number one running back in the country") and Switzer now says he had something like a protocol. Even though, he says, "Within the first week of practice, we know he's he best player we've got," Switzer says he decided not to use him because other players had been waiting to "get in the huddle."

This makes sense for a college team, of course, but Dupree was 19 years old, and mystified by the coaches' decisions. The documentary doesn't explain exactly how the relationships went wrong, as each interview subject has his own version of events, but the upshot is that this astonishing player was not playing, and when the team did change its offense (from a wishbone to an I formation), Dupree was again remarkable. "In every game he was busting a long run," remembers radio reporter Mick Cornett, ""A freshman putting together run after run after run. He immediately became the most popular person in Oklahoma outside of his head coach." Again, footage of Dupree—this time in color—reveals how astounding he was, and why people who saw him were so moved.

Football, as everyone knows, is a brutal game. And it is at least partly premised on luck, as this can ordain which players play, which adults counsel them, where they play and how healthy they are or stay. The Best That Never Was leaves a lot of its story off-screen, focused less on who might be responsible for what or how Marcus ended up at any particular step of his journey, than on his brilliance, however short-lived. He's injured more than once, he's confused, and he's prone to accept less than helpful recommendations. As Switzer sums up, "There was so much more to play and so much more to see we didn't get to." The question the film asks is most pertinent: who made up this "we" and where were they when Marcus Dupree needed them?

The Daily Beast

by Buzz Bissinger

by Buzz Bissinger

Marcus Dupree was pegged to win three Heismans before he got chewed up in the college system. Continue reading

The Daily Beast

by Buzz Bissinger

Winning Night: "Rize" and "Through the Fire"

Marcus Dupree was pegged to win three Heismans before he got chewed up in the college system. How did the high-school sensation make peace with life after football? Buzz Bissinger reports.

Marcus Dupree watched the Super Bowl last Sunday in the place where he grew up, the town of Philadelphia, Mississippi. If there was anyone in the history of football who I thought would be glued to the television, playing the athlete's lament of could-have-should-have, it would have been him. Marcus Dupree, 1982. Credit: Newscom

Because it should have been him. But it wasn't. Because of the college meat grinder that mangles so many players. Because of too much attention for a simple homespun kid whose world revolved around his mother and grandmother and younger brother Reggie, born with cerebral palsy. Because of the pressure of becoming, at 17, the black and white hope who would finally heal the gaping racism of a town in which three young civil-rights workers had been murdered in 1964. Because of recruiters for the University of Oklahoma and the University of Texas who moved into a motel in Philadelphia for weeks to gain any extra edge. Because of Oklahoma Coach Barry Switzer, who after willfully destroying the very essence of Marcus Dupree, now leans back in his oversize chair in his tricked-out study and admits with a shit-eating little smirk that his greatest regret in coaching was the handling of Marcus Dupree. Which nearly 30 years later is not only absolutely meaningless but amoral.

I grew up in the era of Marcus Dupree in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Of all the players I have ever watched in 56 years, no one, no one, has made more of an impression. He was the best high-school football player ever. He was 6-3 and 230 pounds. He could run the 100-yard dash in 9.5 seconds. He set the high-school record for touchdowns with 87 when he played for Philadelphia High. He gained 7,355 yards.

I had forgotten about Marcus Dupree. Until roughly a month ago, when I watched a brilliant documentary on ESPN that was conceived, written, and directed by Jonathan Hock. The title was The Best That Never Was, the moniker forever a noose around Dupree's neck. It all returned as I watched—the speed and power and poetry of the way he ran; the willful puncturing of that by Barry Switzer in the early 1980s; the shift, like so many thousands of athletes coming out of high school, from folk hero to the forgotten. Those very same feelings hit me as I watched the Super Bowl. I truly thought that at some point in Marcus Dupree's 46-year-old life, it would have been him with the MVP trophy and the car and the trip to Disneyland.

He loved playing football. Thanks to remarkable footage Hock discovered from Dupree's high school days, you could see it in the abandon and freedom. Until he went to Oklahoma in 1982.

Almost immediately, Switzer said that Dupree was out of shape, lazy, lacking in intensity. The transition from small-town Mississippi to big-time college football, with the nation watching, was difficult enough. "I was overwhelmed," he recently told me. But it was never a fair fight, Switzer a grown man paid to deal with young athletes and Dupree a teenager who, until a recruiting trip the year before, had never been on an airplane. He needed encouragement to overcome his alienation and moodiness, not vicious swipes.

But Switzer, one of college football's finest hacksaw butchers, still knew a good cut of meat. He knew Dupree was the best running back on the team even if he was a lowly freshman. He knew he had to finally start him. Dupree finished the season with 1,144 yards. In the Fiesta Bowl against Arizona State, he gained 239 yards on 17 carries despite playing roughly half the game because of a hamstring that had never properly healed after he'd torn it in high school. Switzer congratulated the effort by publicly criticizing Dupree for being out of shape because he was caught twice from behind. He said the kid should have gained 400 yards.

He has even made his peace with Barry Switzer, who in another worthless piece of performance art, once turned to Dallas Cowboys Hall of Fame running back Emmitt Smith when he coached there and told him, "You're not the best No. 22 I ever saw."

Before Dupree's sophomore year, Sports Illustrated said he had the possibility of winning the Heisman Trophy the next three seasons. But the relationship between Switzer and Dupree had soured into outright hate. Midway through his sophomore season, Dupree quit the team and never returned to Norman. He went on to play in the old United States Football League. He signed a $6 million contract, almost none of which he actually saw. But in his second season he suffered a horrifying knee injury that left him in a cast for five months.

He went back to Philadelphia. He sat by himself in a darkened room and refused to see anyone. He looked like an old man and weighed almost 300 pounds. Reluctantly he was coaxed into going to a New Orleans Saints game. He got a sideline pass. He looked up in wonderment and heard the ceaseless noise of frenzy. He remembered.

In a makeshift gym in his grandmother's house, using ancient equipment, he worked himself back into shape. His work ethic, contrary to Switzer's endless derision, reflected a savage intensity. Miraculously, after a five-and-a-half year absence, he made the Los Angeles Rams. He played two seasons and he only scored one touchdown. But it proved that nobody could ever call him a quitter—except a coach who, regardless of the mea culpas he gave in the documentary, obviously didn't like him and didn't want him, a piece of meat in college football that could always be replaced by another one fresh and dangling on the hook.

Marcus Dupree has worked as a truck driver. Most recently he was the foreman of a crew in Mississippi that helped to clean up the BP oil spill. It was not the life he ever envisioned, the beauty of his running in high school so tinged by the bittersweet.

Most athletes would be bitter and angry until the end of their days. But Dupree has never done that. He is proud that he made it to the National Football League. He has even made his peace with Barry Switzer, who in another worthless piece of performance art, once turned to Dallas Cowboys Hall of Fame running back Emmitt Smith when he coached there and told him, "You're not the best No. 22 I ever saw."

When Marcus Dupree is given a compliment, the first thing he does is laugh from the heart. Then he offers thanks. "You don't know in life what you're going to be," he said. "There's life after football. I just thank God I grew up."

He barely watched last Sunday's Super Bowl, simply because he had other priorities. It was his grandson's 7th birthday and there was a party at the new Depot bowling alley in Philadelphia. He did catch the last five minutes of the game, and he was impressed by the poise of Green Bay Packers' quarterback Aaron Rodgers. But there was no jealousy. There was no regret. With 15 wired-up kids on his hands, he had a lot more to worry about.

Which is the truest definition of greatness anyway.

by Buzz Bissinger

Winning Night: "Rize" and "Through the Fire"

Marcus Dupree was pegged to win three Heismans before he got chewed up in the college system. How did the high-school sensation make peace with life after football? Buzz Bissinger reports.

Marcus Dupree watched the Super Bowl last Sunday in the place where he grew up, the town of Philadelphia, Mississippi. If there was anyone in the history of football who I thought would be glued to the television, playing the athlete's lament of could-have-should-have, it would have been him. Marcus Dupree, 1982. Credit: Newscom

Because it should have been him. But it wasn't. Because of the college meat grinder that mangles so many players. Because of too much attention for a simple homespun kid whose world revolved around his mother and grandmother and younger brother Reggie, born with cerebral palsy. Because of the pressure of becoming, at 17, the black and white hope who would finally heal the gaping racism of a town in which three young civil-rights workers had been murdered in 1964. Because of recruiters for the University of Oklahoma and the University of Texas who moved into a motel in Philadelphia for weeks to gain any extra edge. Because of Oklahoma Coach Barry Switzer, who after willfully destroying the very essence of Marcus Dupree, now leans back in his oversize chair in his tricked-out study and admits with a shit-eating little smirk that his greatest regret in coaching was the handling of Marcus Dupree. Which nearly 30 years later is not only absolutely meaningless but amoral.

I grew up in the era of Marcus Dupree in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Of all the players I have ever watched in 56 years, no one, no one, has made more of an impression. He was the best high-school football player ever. He was 6-3 and 230 pounds. He could run the 100-yard dash in 9.5 seconds. He set the high-school record for touchdowns with 87 when he played for Philadelphia High. He gained 7,355 yards.

I had forgotten about Marcus Dupree. Until roughly a month ago, when I watched a brilliant documentary on ESPN that was conceived, written, and directed by Jonathan Hock. The title was The Best That Never Was, the moniker forever a noose around Dupree's neck. It all returned as I watched—the speed and power and poetry of the way he ran; the willful puncturing of that by Barry Switzer in the early 1980s; the shift, like so many thousands of athletes coming out of high school, from folk hero to the forgotten. Those very same feelings hit me as I watched the Super Bowl. I truly thought that at some point in Marcus Dupree's 46-year-old life, it would have been him with the MVP trophy and the car and the trip to Disneyland.

He loved playing football. Thanks to remarkable footage Hock discovered from Dupree's high school days, you could see it in the abandon and freedom. Until he went to Oklahoma in 1982.

Almost immediately, Switzer said that Dupree was out of shape, lazy, lacking in intensity. The transition from small-town Mississippi to big-time college football, with the nation watching, was difficult enough. "I was overwhelmed," he recently told me. But it was never a fair fight, Switzer a grown man paid to deal with young athletes and Dupree a teenager who, until a recruiting trip the year before, had never been on an airplane. He needed encouragement to overcome his alienation and moodiness, not vicious swipes.

But Switzer, one of college football's finest hacksaw butchers, still knew a good cut of meat. He knew Dupree was the best running back on the team even if he was a lowly freshman. He knew he had to finally start him. Dupree finished the season with 1,144 yards. In the Fiesta Bowl against Arizona State, he gained 239 yards on 17 carries despite playing roughly half the game because of a hamstring that had never properly healed after he'd torn it in high school. Switzer congratulated the effort by publicly criticizing Dupree for being out of shape because he was caught twice from behind. He said the kid should have gained 400 yards.

He has even made his peace with Barry Switzer, who in another worthless piece of performance art, once turned to Dallas Cowboys Hall of Fame running back Emmitt Smith when he coached there and told him, "You're not the best No. 22 I ever saw."

Before Dupree's sophomore year, Sports Illustrated said he had the possibility of winning the Heisman Trophy the next three seasons. But the relationship between Switzer and Dupree had soured into outright hate. Midway through his sophomore season, Dupree quit the team and never returned to Norman. He went on to play in the old United States Football League. He signed a $6 million contract, almost none of which he actually saw. But in his second season he suffered a horrifying knee injury that left him in a cast for five months.

He went back to Philadelphia. He sat by himself in a darkened room and refused to see anyone. He looked like an old man and weighed almost 300 pounds. Reluctantly he was coaxed into going to a New Orleans Saints game. He got a sideline pass. He looked up in wonderment and heard the ceaseless noise of frenzy. He remembered.

In a makeshift gym in his grandmother's house, using ancient equipment, he worked himself back into shape. His work ethic, contrary to Switzer's endless derision, reflected a savage intensity. Miraculously, after a five-and-a-half year absence, he made the Los Angeles Rams. He played two seasons and he only scored one touchdown. But it proved that nobody could ever call him a quitter—except a coach who, regardless of the mea culpas he gave in the documentary, obviously didn't like him and didn't want him, a piece of meat in college football that could always be replaced by another one fresh and dangling on the hook.

Marcus Dupree has worked as a truck driver. Most recently he was the foreman of a crew in Mississippi that helped to clean up the BP oil spill. It was not the life he ever envisioned, the beauty of his running in high school so tinged by the bittersweet.

Most athletes would be bitter and angry until the end of their days. But Dupree has never done that. He is proud that he made it to the National Football League. He has even made his peace with Barry Switzer, who in another worthless piece of performance art, once turned to Dallas Cowboys Hall of Fame running back Emmitt Smith when he coached there and told him, "You're not the best No. 22 I ever saw."

When Marcus Dupree is given a compliment, the first thing he does is laugh from the heart. Then he offers thanks. "You don't know in life what you're going to be," he said. "There's life after football. I just thank God I grew up."

He barely watched last Sunday's Super Bowl, simply because he had other priorities. It was his grandson's 7th birthday and there was a party at the new Depot bowling alley in Philadelphia. He did catch the last five minutes of the game, and he was impressed by the poise of Green Bay Packers' quarterback Aaron Rodgers. But there was no jealousy. There was no regret. With 15 wired-up kids on his hands, he had a lot more to worry about.

Which is the truest definition of greatness anyway.