The Wall Street Journal

by Michael Judge

by Michael Judge

One of the main attractions of sports is that they're a welcome escape from the politics of the day and the things men do to one another in the name of this or that cause. Occasionally, however, the world of sports and politics collide. And when they do, it's usually without a happy outcome—think of the 1972 Munich Olympics, when 11 Israeli athletes were murdered by Palestinian terrorists; Jimmy Carter's boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics; and the subsequent Soviet boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. Continue reading

The Wall Street Journal

by Michael Judge

One of the main attractions of sports is that they're a welcome escape from the politics of the day and the things men do to one another in the name of this or that cause. Occasionally, however, the world of sports and politics collide. And when they do, it's usually without a happy outcome—think of the 1972 Munich Olympics, when 11 Israeli athletes were murdered by Palestinian terrorists; Jimmy Carter's boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics; and the subsequent Soviet boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

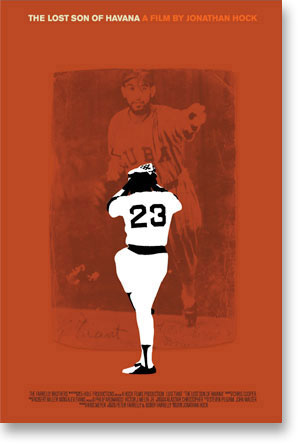

Pitching great Luis Tiant, the subject of ESPN's "The Lost Son of Havana."

It should come as no surprise then, that "The Lost Son of Havana," an ESPN Films documentary about Red Sox pitching great Luis Tiant's return to Cuba after 46 years of exile, is not a happy tale (Sunday, 6 p.m.-8 p.m. ET on ESPN Deportes; Monday, 10 p.m. ET on ESPN). It is, rather, the story of a refugee's rise to major-league stardom and the torment of returning home decades later to visit family on an island gulag.

"Things could have been different," says Mr. Tiant, overcome with emotion at his aunt's cramped and run-down Havana home. He is, of course, right. The wealth he accumulated in the major leagues could have helped lift his entire family out of poverty. But Castro's revolution dashed any hopes he might have had of playing professionally in his country or returning home to help support his family and the community he left behind. In 2007, he was finally allowed back into Cuba as part of a goodwill baseball game between American amateurs and retired Cuban players.

Written and directed by documentary filmmaker Jonathan Hock, "The Lost Son" begins with a shot of the 67-year-old Mr. Tiant puffing on a cigar and examining an old black-and-white photo of his father, Luis Tiant Sr., a baseball great in his own right who pitched in America's Negro League in the 1930s and '40s. Luis Sr. didn't have an overwhelming fastball but was, like his son, an absolute master of the screwball and other off-speed pitches. With his "herky-jerky" windup and off-beat delivery, he dominated the Negro League and twice defeated the Babe Ruth All-Stars in exhibition play, holding the Babe to just one single.

There's no doubt that Luis Tiant Sr. had the stuff to be a star in the majors. But by the time Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, Luis Sr.'s professional baseball career was over and he was forced to return home to Havana.

The dream of playing in the major leagues, however, lived on in his son, and in the summer of 1961 Luis Jr. left Havana for a three-month stint in the Mexican league, where he hoped to be discovered by an American scout. He quickly became a sensation and it wasn't long before the Cleveland Indians signed him to a minor-league contract.

"But that was also the summer of the invasion of the Bay of Pigs," the film's narrator, actor Chris Cooper, explains over old footage of the failed U.S. invasion. "Cuba and the United States severed relations, and Castro tightened his control over every aspect of Cuban life. Suddenly no Cuban was free to leave the island. Cubans playing baseball overseas received an ultimatum: Come home and play as amateurs in Cuba or never come home again: And so, Luis's three-month trip became 46 years of exile."

Through interviews with sportswriters, former teammates and footage from scores of games, the film documents the dramatic ups and downs of Mr. Tiant's 19-year career, including the 1970 injury (a fractured scapula) that nearly ended his playing days; his remarkable climb back to the majors (he taught himself to pitch again, it seems, by imitating his father's wild windup and off-speed pitches); and his winning starts for the Red Sox in the 1975 World Series, which Boston lost to Cincinnati 3-4.

TV Listings

Find television listings at LocateTV .

But it is the sounds and images of his return to Cuba that are most poignant, and elevate the film to far more than a sports documentary. Antique cars and dilapidated buildings abound. Ordinary household goods are nearly impossible to come by. Like most Cubans, Mr. Tiant's aunts and cousins receive enough staple goods from the government each month to last about 15 days; they must "improvise" for the rest. Not surprisingly, the black market is thriving and U.S. dollars are the currency of choice. One relative tells Mr. Tiant, holding back tears, "We are living on cigarettes."

Knowing they're in need, Mr. Tiant brings a suitcase full of gifts and basic supplies such as clothing, toothpaste, sewing kits and medicine. And though we only see him give money to one relative, one suspects he brought a thick wad of greenbacks with him as well.

Sadly, there's an air of resentment among some. When an old neighbor says he was "forgetful" of his family, Mr. Tiant disagrees and explains that he sent gifts, money and supplies but they were always confiscated by the Cuban authorities. Still, his sense of regret at not doing enough for his family in Cuba is apparent, even though it was Luis Sr. who told him over and over again never to return, to live the life his father couldn't.

Amazingly, there's more to the story. In 1975, not long before the World Series, Castro (by all accounts a genuine baseball fan) gave Mr. Tiant's parents a special visa to travel to America. Sen. George McGovern, as he testifies in the film, hand-delivered a letter from Luis Jr. to Castro asking that he allow his parents to travel to the U.S. to see him play. For whatever reason, Castro granted his request, and Luis's parents came to America and lived with him until their all-too-early deaths the following year.

Nevertheless, a few days after his arrival in Boston, Luis Tiant Sr. was invited to throw out the ceremonial first pitch in a game against the California Angels at Fenway Park—a perfect strike. As he and his son stood together on the mound at Fenway, 30,000 adoring fans chanted "Luis! Luis! Luis!"—a glorious, and one hopes for a father and son from Havana, healing moment in baseball history.

—Mr. Judge is a freelance writer in Iowa.

by Michael Judge

One of the main attractions of sports is that they're a welcome escape from the politics of the day and the things men do to one another in the name of this or that cause. Occasionally, however, the world of sports and politics collide. And when they do, it's usually without a happy outcome—think of the 1972 Munich Olympics, when 11 Israeli athletes were murdered by Palestinian terrorists; Jimmy Carter's boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics; and the subsequent Soviet boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

Pitching great Luis Tiant, the subject of ESPN's "The Lost Son of Havana."

It should come as no surprise then, that "The Lost Son of Havana," an ESPN Films documentary about Red Sox pitching great Luis Tiant's return to Cuba after 46 years of exile, is not a happy tale (Sunday, 6 p.m.-8 p.m. ET on ESPN Deportes; Monday, 10 p.m. ET on ESPN). It is, rather, the story of a refugee's rise to major-league stardom and the torment of returning home decades later to visit family on an island gulag.

"Things could have been different," says Mr. Tiant, overcome with emotion at his aunt's cramped and run-down Havana home. He is, of course, right. The wealth he accumulated in the major leagues could have helped lift his entire family out of poverty. But Castro's revolution dashed any hopes he might have had of playing professionally in his country or returning home to help support his family and the community he left behind. In 2007, he was finally allowed back into Cuba as part of a goodwill baseball game between American amateurs and retired Cuban players.

Written and directed by documentary filmmaker Jonathan Hock, "The Lost Son" begins with a shot of the 67-year-old Mr. Tiant puffing on a cigar and examining an old black-and-white photo of his father, Luis Tiant Sr., a baseball great in his own right who pitched in America's Negro League in the 1930s and '40s. Luis Sr. didn't have an overwhelming fastball but was, like his son, an absolute master of the screwball and other off-speed pitches. With his "herky-jerky" windup and off-beat delivery, he dominated the Negro League and twice defeated the Babe Ruth All-Stars in exhibition play, holding the Babe to just one single.

There's no doubt that Luis Tiant Sr. had the stuff to be a star in the majors. But by the time Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, Luis Sr.'s professional baseball career was over and he was forced to return home to Havana.

The dream of playing in the major leagues, however, lived on in his son, and in the summer of 1961 Luis Jr. left Havana for a three-month stint in the Mexican league, where he hoped to be discovered by an American scout. He quickly became a sensation and it wasn't long before the Cleveland Indians signed him to a minor-league contract.

"But that was also the summer of the invasion of the Bay of Pigs," the film's narrator, actor Chris Cooper, explains over old footage of the failed U.S. invasion. "Cuba and the United States severed relations, and Castro tightened his control over every aspect of Cuban life. Suddenly no Cuban was free to leave the island. Cubans playing baseball overseas received an ultimatum: Come home and play as amateurs in Cuba or never come home again: And so, Luis's three-month trip became 46 years of exile."

Through interviews with sportswriters, former teammates and footage from scores of games, the film documents the dramatic ups and downs of Mr. Tiant's 19-year career, including the 1970 injury (a fractured scapula) that nearly ended his playing days; his remarkable climb back to the majors (he taught himself to pitch again, it seems, by imitating his father's wild windup and off-speed pitches); and his winning starts for the Red Sox in the 1975 World Series, which Boston lost to Cincinnati 3-4.

TV Listings

Find television listings at LocateTV .

But it is the sounds and images of his return to Cuba that are most poignant, and elevate the film to far more than a sports documentary. Antique cars and dilapidated buildings abound. Ordinary household goods are nearly impossible to come by. Like most Cubans, Mr. Tiant's aunts and cousins receive enough staple goods from the government each month to last about 15 days; they must "improvise" for the rest. Not surprisingly, the black market is thriving and U.S. dollars are the currency of choice. One relative tells Mr. Tiant, holding back tears, "We are living on cigarettes."

Knowing they're in need, Mr. Tiant brings a suitcase full of gifts and basic supplies such as clothing, toothpaste, sewing kits and medicine. And though we only see him give money to one relative, one suspects he brought a thick wad of greenbacks with him as well.

Sadly, there's an air of resentment among some. When an old neighbor says he was "forgetful" of his family, Mr. Tiant disagrees and explains that he sent gifts, money and supplies but they were always confiscated by the Cuban authorities. Still, his sense of regret at not doing enough for his family in Cuba is apparent, even though it was Luis Sr. who told him over and over again never to return, to live the life his father couldn't.

Amazingly, there's more to the story. In 1975, not long before the World Series, Castro (by all accounts a genuine baseball fan) gave Mr. Tiant's parents a special visa to travel to America. Sen. George McGovern, as he testifies in the film, hand-delivered a letter from Luis Jr. to Castro asking that he allow his parents to travel to the U.S. to see him play. For whatever reason, Castro granted his request, and Luis's parents came to America and lived with him until their all-too-early deaths the following year.

Nevertheless, a few days after his arrival in Boston, Luis Tiant Sr. was invited to throw out the ceremonial first pitch in a game against the California Angels at Fenway Park—a perfect strike. As he and his son stood together on the mound at Fenway, 30,000 adoring fans chanted "Luis! Luis! Luis!"—a glorious, and one hopes for a father and son from Havana, healing moment in baseball history.

—Mr. Judge is a freelance writer in Iowa.

Ain't It Cool News

by Mr. Beaks

by Mr. Beaks

What if you reached the pinnacle of your professional career, but knew that your mother and father - the two people most responsible for helping you realize your dream - were locked away in a prison, unable to share in your success and, perhaps, unaware of your accomplishments? It'd break your heart, right?

Continue reading

Continue reading

Ain't It Cool News

by Mr. Beaks

Tribeca Film Festival '09: Mr. Beaks Journeys To Cuba With Luis Tiant, THE LOST SON OF HAVANA!

What if you reached the pinnacle of your professional career, but knew that your mother and father - the two people most responsible for helping you realize your dream - were locked away in a prison, unable to share in your success and, perhaps, unaware of your accomplishments? It'd break your heart, right?

That's essentially what Luis Tiant had to contend with throughout the bulk of his major league baseball career as a starting pitcher for the Cleveland Indians, Minnesota Twins and Boston Red Sox. While "El Tiante" was establishing himself as an unstoppable force on the mound for the Indians from 1964 to 1969 (a hapless squad that only once finished above fifth place during that period), his parents were living under the totalitarian rule of Fidel Castro in Cuba. Were they aware of his progress? Were they proud? Were they well? Save for censored correspondence, Tiant had no way of knowing how any of his loved ones were faring under Castro's dictatorship - and, save for pirate radio/TV broadcasts, they had no way of knowing whether their beloved Luis was thriving or failing in the United States.

If all you know of Tiant's career are his unique back-to-the-plate delivery* and his 1970s comeback with the Red Sox, which peaked with his heroic battle with the Big Red Machine in the 1975 World Series - or if you don't know his story at all - then you need to see Jonathan Hock's heartfelt documentary THE LOST SON OF HAVANA. Based around Tiant's 2007 return to Cuba - his first trip home in forty-six years - Hock's film works as both a Tiant family history and a humanistic, albeit deftly apolitical, examination of the poverty-stricken country during what are surely the last days of Castro's reign. Though an absolute must for baseball fans, who'll once again get caught up in the drama of that epic 1975 postseason tilt, it's also a heartbreaking account of a late-in-life family reunion, with Tiant reconnecting and, in several instances, possibly bidding farewell to the loved ones he left behind all those years ago.

The gulf between Tiant's comfortable lifestyle in the U.S., where he currently works as a pitching advisor for the Red Sox, and the squalid living conditions of his surviving aunts and uncles and cousins and nephews is, of course, stunning. It's also the basis for a good deal of dramatic tension, particularly when Tiant first begins kicking around his old neighborhood and encounters an old acquaintance. Though the man is at first pleased to see the pitching legend, he abruptly works into a rage that's fueled by resentment for Tiant leaving and the impossible conditions under which he's had to subsist for the past six decades. Though most of Tiant's relatives express no bitterness, you get the sense that there is some unspoken anger here - especially when Tiant begins handing out "extravagances" like Pepto-Bismol, chewing gum and shampoo. These gifts go over well early on, but they're mere tokens of goodwill; later on, bolder family members will hit Tiant up for cash.

But if anyone can understand this kind of practicality, it's Tiant, who affects a strictly-business swagger with his ever-present dark sunglasses and customary cigar clenched between his teeth. For much of the film, Tiant is impassive; most likely, this is byproduct of having to shut out tragic circumstances in order to excel during one of the baseball's most competitive eras. But there's a big, wounded heart beating beneath this tough exterior. And when Tiant lets his emotional guard down, it's impossible to not weep with him.

Generally, Tiant's sadness derives from the absence of family during the prime of his career. This pain is particularly acute because his father, Luis Sr., was a dominant pitcher for the Negro League's New York Cubans from 1926 to 1948. In other words, his father had already made sacrifices to help pave the way for Tiant's success in the integrated major leagues; though Luis Sr. occasionally got to show his stuff against the best in the game (there's a great story of a showdown with Babe Ruth), he was never able to do it on a consistent basis. So Tiant was living two dreams when he made it to the bigs. Sadly, most of this dream (at least until the 1970s) was little more than a rumor to the elder Luis.

What's most impressive about Hock's film is the way it refuses to use El Tiante's triumphant 1975 season as easy, unearned uplift. Yes, his domination of the Cincinnati Reds offsets a good deal of the tragedy in the pitcher's life, but it's not the end of his journey by a long shot. And while it's nice that Hock and company were crafty enough to get around the U.S.-imposed travel restrictions, Tiant's brief stay in Cuba does not wipe away forty-six years of regret - nor does it do much for the Tiants struggling to survive in the economically depressed country. And that's where Hock pulls off something kind of miraculous: rather than indulge in easy political rhetoric (or, worse, ignore the injustice altogether by closing the book on Tiant's relationship to his homeland once his visit is over), he makes this about the people. Slowly, the idea of maintaining, at the very least, the travel ban in the dying days of the Castro dictatorship becomes indefensible. At this point, it's an act of unintentional cruelty. One look at the sorry state of Cuba in Hock's film, and it's clear that the U.S. won. Want to rub this victory in Castro's face? Show his people mercy while he's still alive. Do it for the Tiants and all the other families who've spent half a century hoping to reconnect with their loved ones before it's too late.

THE LOST SON OF HAVANA premieres Thursday, April 23rd, at the Tribeca Film Festival. It will screen again on the 27th, the 30th and May 2nd. Tickets are available via the festival's official site.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks

by Mr. Beaks

Tribeca Film Festival '09: Mr. Beaks Journeys To Cuba With Luis Tiant, THE LOST SON OF HAVANA!

What if you reached the pinnacle of your professional career, but knew that your mother and father - the two people most responsible for helping you realize your dream - were locked away in a prison, unable to share in your success and, perhaps, unaware of your accomplishments? It'd break your heart, right?

That's essentially what Luis Tiant had to contend with throughout the bulk of his major league baseball career as a starting pitcher for the Cleveland Indians, Minnesota Twins and Boston Red Sox. While "El Tiante" was establishing himself as an unstoppable force on the mound for the Indians from 1964 to 1969 (a hapless squad that only once finished above fifth place during that period), his parents were living under the totalitarian rule of Fidel Castro in Cuba. Were they aware of his progress? Were they proud? Were they well? Save for censored correspondence, Tiant had no way of knowing how any of his loved ones were faring under Castro's dictatorship - and, save for pirate radio/TV broadcasts, they had no way of knowing whether their beloved Luis was thriving or failing in the United States.

If all you know of Tiant's career are his unique back-to-the-plate delivery* and his 1970s comeback with the Red Sox, which peaked with his heroic battle with the Big Red Machine in the 1975 World Series - or if you don't know his story at all - then you need to see Jonathan Hock's heartfelt documentary THE LOST SON OF HAVANA. Based around Tiant's 2007 return to Cuba - his first trip home in forty-six years - Hock's film works as both a Tiant family history and a humanistic, albeit deftly apolitical, examination of the poverty-stricken country during what are surely the last days of Castro's reign. Though an absolute must for baseball fans, who'll once again get caught up in the drama of that epic 1975 postseason tilt, it's also a heartbreaking account of a late-in-life family reunion, with Tiant reconnecting and, in several instances, possibly bidding farewell to the loved ones he left behind all those years ago.

The gulf between Tiant's comfortable lifestyle in the U.S., where he currently works as a pitching advisor for the Red Sox, and the squalid living conditions of his surviving aunts and uncles and cousins and nephews is, of course, stunning. It's also the basis for a good deal of dramatic tension, particularly when Tiant first begins kicking around his old neighborhood and encounters an old acquaintance. Though the man is at first pleased to see the pitching legend, he abruptly works into a rage that's fueled by resentment for Tiant leaving and the impossible conditions under which he's had to subsist for the past six decades. Though most of Tiant's relatives express no bitterness, you get the sense that there is some unspoken anger here - especially when Tiant begins handing out "extravagances" like Pepto-Bismol, chewing gum and shampoo. These gifts go over well early on, but they're mere tokens of goodwill; later on, bolder family members will hit Tiant up for cash.

But if anyone can understand this kind of practicality, it's Tiant, who affects a strictly-business swagger with his ever-present dark sunglasses and customary cigar clenched between his teeth. For much of the film, Tiant is impassive; most likely, this is byproduct of having to shut out tragic circumstances in order to excel during one of the baseball's most competitive eras. But there's a big, wounded heart beating beneath this tough exterior. And when Tiant lets his emotional guard down, it's impossible to not weep with him.

Generally, Tiant's sadness derives from the absence of family during the prime of his career. This pain is particularly acute because his father, Luis Sr., was a dominant pitcher for the Negro League's New York Cubans from 1926 to 1948. In other words, his father had already made sacrifices to help pave the way for Tiant's success in the integrated major leagues; though Luis Sr. occasionally got to show his stuff against the best in the game (there's a great story of a showdown with Babe Ruth), he was never able to do it on a consistent basis. So Tiant was living two dreams when he made it to the bigs. Sadly, most of this dream (at least until the 1970s) was little more than a rumor to the elder Luis.

What's most impressive about Hock's film is the way it refuses to use El Tiante's triumphant 1975 season as easy, unearned uplift. Yes, his domination of the Cincinnati Reds offsets a good deal of the tragedy in the pitcher's life, but it's not the end of his journey by a long shot. And while it's nice that Hock and company were crafty enough to get around the U.S.-imposed travel restrictions, Tiant's brief stay in Cuba does not wipe away forty-six years of regret - nor does it do much for the Tiants struggling to survive in the economically depressed country. And that's where Hock pulls off something kind of miraculous: rather than indulge in easy political rhetoric (or, worse, ignore the injustice altogether by closing the book on Tiant's relationship to his homeland once his visit is over), he makes this about the people. Slowly, the idea of maintaining, at the very least, the travel ban in the dying days of the Castro dictatorship becomes indefensible. At this point, it's an act of unintentional cruelty. One look at the sorry state of Cuba in Hock's film, and it's clear that the U.S. won. Want to rub this victory in Castro's face? Show his people mercy while he's still alive. Do it for the Tiants and all the other families who've spent half a century hoping to reconnect with their loved ones before it's too late.

THE LOST SON OF HAVANA premieres Thursday, April 23rd, at the Tribeca Film Festival. It will screen again on the 27th, the 30th and May 2nd. Tickets are available via the festival's official site.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks